6e. How a Bill Becomes a Law

Congresswoman Barbara Lee speaks in favor of legislation for campaign finance reform. Speaking in the well of the House of Representatives is a typical part of the debate process on new bills.

Creating legislation is what the business of Congress is all about. Ideas for laws come from many places — ordinary citizens, the president, offices of the executive branch, state legislatures and governors, congressional staff, and of course the members of Congress themselves.

Constitutional provisions, whose primary purposes are to create obstacles, govern the process that a bill goes through before it becomes law. The founders believed that efficiency was the hallmark of oppressive government, and they wanted to be sure that laws that actually passed all the hurdles were the well considered result of inspection by many eyes.

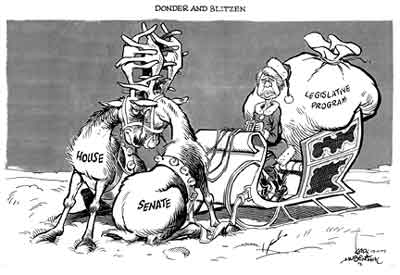

Former President Jimmy Carter is characterized here as a Santa Claus whose presents to the people are held up by Congress locking horns.

Before a bill becomes a law it must pass both houses of Congress and signed into law by the President. It may begin its journey at any time, but it must be passed during the same congressional session of its proposal, a period of one year. If it does not complete the process, it is dropped, and can only be revived through reintroduction and going through the whole process again. Not surprisingly, less that 10% of proposed bills actually become laws.

There are many opportunities to kill a bill before it becomes law. In each house, a bill must survive three stages:

- Committee consideration — New bills are sent to standing committees by subject matter. For example, bills on farm subsidies generally go to the Agriculture Committee. Bills that propose tax changes would go to the House Ways and Means Committee. Since the volume of bills is so large, most bills today are sent directly to subcommittee. Most bills — about 90% — die in committee or subcommittee, where they are pigeonholed, or simply forgotten and never discussed. If a bill survives, hearings are set up in which various experts, government officials, or lobbyists present their points of view to committee members. After the hearings, the bill is marked up, or revised, until the committee is ready to send it to the floor.

The filibuster king Strom Thurmond kept the Senate floor for over one day, with only one brief bathroom break. - Floor debate — In the House only, a bill goes from committee to a special Rules Committee that sets time limits on debate and rules for adding amendments. If time limits are short and no amendments are allowed from the floor, the powerful rules committee is said to have imposed a "gag rule." Rules for debate on the Senate floor are much looser, with Senators being allowed to talk as much about each bill as they like. No restrictions on amendments are allowed in the Senate. This lack of rules has led to an occasional filibuster in which a senator literally talks a bill to death. Filibusters are prohibited in the House. Both houses require a quorum (majority) of its members to be present for a vote. Passage of a bill generally requires a majority vote by the members present.

- Conference committees — Most bills that pass the first two stages do not need to go to conference committee, but those that are controversial, particularly important, or complex often do. A conference committee is formed to merge two versions of a bill — one from the House and one from the Senate — when the two houses cannot readily agree on alterations. The members are chosen from the standing committees that sponsored the bill who come up with a compromise. The revised bill then must go back to the floors of each house and be passed by both houses before it can be sent to the President for signing.

When bills are marked up, in Congress, they may be changed to sneak in unapproved spending or overspending on programs. The spending is called "pork" and the tactic, "pork barreling."

Many people criticize Congress for its inefficiency and the length of time that it takes for laws to be passed and enacted. Although the process is long and difficult, the founders intentionally set it up that way. Some modern critics believe that the system is arcane and simply too slow for a fast-paced country like the United States. A process in which only a few people were responsible for making laws certainly would be more efficient. But of course it wouldn't be very democratic. The many hurdles that bills must face help to ensure that those that survive are not just passed on a whim, but are well considered and deliberate.