8a. The Development of the Bureaucracy

Andrew Jackson cemented the spoils system (also called rotation-in-office) during his presidency. He formed his own group of advisors from his friends and political allies, known as the "Kitchen Cabinet," to support his goals for the nation.

The original bureaucracy of the federal government consisted only of employees from three small departments — State, Treasury, and War. The executive branch employs today almost three million people. Not only have the numbers of bureaucrats grown, but also the methods and standards for hiring and promoting people have changed dramatically.

Patronage

George Washington promised to hire only people "as shall be the best qualified." Still, most of his employees belonged to the budding Federalist Party — the party toward which Washington leaned. When Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson became President, he dismissed many of the Federalists and filled their jobs with members from his party. With this action, he began a long tradition of filling government positions through patronage, a system of rewarding friends and political allies in exchange for their support.

Andrew Jackson is regarded as the President who entrenched the patronage, or "spoils" system. Following the old saying, "to the victor go the spoils," he brought a whole new group of "Jacksonian Democrats" into office. Jackson argued that the spoils system brought greater rotation in office. He thought it was healthy to clear out the government workers who had worked for predecessors, lest they become corrupt.

The U.S. Postal Service has changed along with the nation. From the Pony Express to today's uniformed postal workers, these bureaucrats deliver the mail every day, regardless of the weather.

During the 1800s, while more and more federal employees were landing their jobs through patronage, the bureaucracy was growing rapidly as new demands were placed on government. As the country expanded westward new agencies were needed to manage the land and its settlement. And as people moved into the new areas, a greatly expanded Post Office was necessary. The Civil War sparked the creation of thousands of government jobs and new departments to handle the demands of warfare. After the war, the Industrial Revolution encouraged economic growth and more government agencies to regulate the expanding economy.

The Pendleton Act

The spoils tradition was diluted in 1881 when Charles Guiteau, a disappointed office seeker, killed President James Garfield because he was not granted a government job. After Garfield's assassination, Congress passed the Pendleton Act, which created a merit-based federal civil service. It was meant to replace patronage with the principle of federal employment on the basis of open, competitive exams. The Pendleton Act created a three-member Civil Service Commission to administer this new merit system. At first only about 10 percent of federal employees were members of the civil service. Today, about 85 to 90 percent take this exam.

Growth in the 20th Century

In reaction to the excesses of Gilded Age millionaires, many Americans demanded that the government regulate business and industry. As a result, a group of independent regulatory commissions emerged as the 20th century dawned. The first of these agencies was the Interstate Commerce Commission, set up in 1887 to monitor abuses in the railroad industry. Reform movements of the early 20th century demanded that government regulate child labor, food processing and packaging, and working and living conditions for the laboring classes.

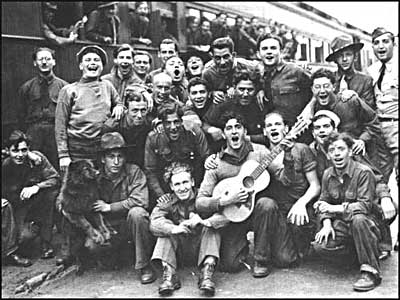

The Civilian Conservation Corps was part of Roosevelt's New Deal programs to battle the Depression. Aimed at employing men between the ages of 18 and 25, over 3,000,000 men joined the CCC and became members of the federal bureaucracy between 1933 and 1941.

The largest growth of the bureaucracy in American history came between 1933 and 1945. Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal meant bigger government, since agencies were needed to administer his many programs. With the American entry into World War II in 1941, the needs of the war elevated the number of federal agencies and employees even more. During those 12 Roosevelt years, the total number of federal employees increased from a little over half a million in 1933 to an all time high of more than 3.5 million in 1945.

After World War II ended in 1945, the total number of federal employees decreased significantly, but still has remained at levels between about 2.5 and 3 million. Contrary to popular opinion, the federal bureaucracy did not grow in numbers significantly during the last half of the 20th century. Federal bureaucrats did, however, greatly increase their influence.