9b. The Structure of the Federal Courts

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. -Article III, Section 1, The Constitution of the United States

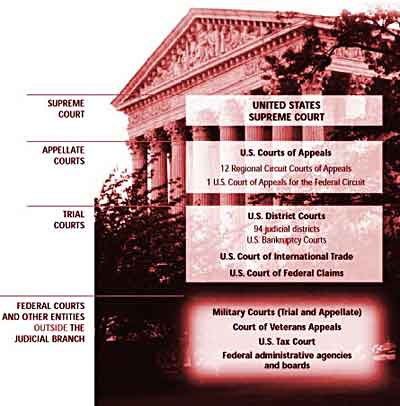

In the federal court system the Supreme Court has final appellate jurisdiction over all courts in the United States.

Notice that, according to the Constitution, Congress creates courts.

By implication, Congress also has the power to reorganize and even dismantle the court system. This clause provides one of many examples of the checks and balances in the Constitution, but it also reveals the Founders' intent to grant greater powers to the legislative branch than to the judicial.

The fact that most of the basic court structure has changed little since it was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789 is an indication that Congress does not readily use this power. The relative independence of the court system, as well as the evolutionary power of the judicial branch, has been generally respected by members of subsequent Congresses.

Constitutional Courts

Courts established by the Judiciary Act of 1789 are called constitutional courts because they are mentioned in Article III (they are the "inferior courts" in the quote above).

Judges who preside over these courts are nominated by the president, confirmed by the Senate, and serve lifetime terms as long as they exhibit "good behavior." Over the years, Congress has created other courts to handle cases for special purposes.

The first Territorial Supreme Court was formed for the Dakota Territory in 1861, but didn't meet to hear appeals until 1867. This photograph shows the members of the court meeting to conduct business for the first time.

Legislative Courts

Those latter courts are referred to as "legislative courts." For example, by the early 20th century, Congress had set up the U.S. territorial courts to hear federal cases in the territories that the United States began acquiring during the late 1800s. Judges for legislative courts are also appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, but they serve fixed, limited terms.

The Judicial Circuits

The Eighth Circuit includes the states of Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

The federal court system is divided into 12 geographic circuits. For example, Circuit One includes the New England states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. Circuit Nine includes seven states in the far western part of the country. Originally, each state in each circuit was to have one district court, where all federal cases from the state originated.

Over time, as the population grew, additional district courts were added. Today, a total of 94 district courts exist; they are staffed by more than 600 judges. Some circuits have more than others, based on population, but each circuit still has only one court of appeals. Cases not settled in the courts of appeal may be appealed further, but only to the Supreme Court.

District Courts and Courts of Appeals

Each U.S. district court has a different seal, a different jurisdiction, and different local rules.

Most cases that deal with federal questions or offenses begin in district courts, which are almost always granted original jurisdiction. District courts hear appeals cases only in the rare case of a constitutional question that may arise in state courts. About 80 percent of all federal cases are heard in district courts, and most of them end there. The number of judges assigned to district courts varies from two to twenty-eight, depending on caseloads and population.

Courts of Appeal

By the late 19th century, so many people were appealing their cases to the Supreme Court that Congress created another type of constitutional court, the courts of appeals. Today, along with 12 courts of appeals (one for each circuit), a thirteenth court, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, hears cases that deal with patents, contracts, and financial claims against the federal government.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, located in San Fransisco, is noted not only for its legal importance but its ornate architecture.

Courts of appeals never hear cases on original jurisdiction, and most appeals come from district courts within their circuits. They do sometimes hear cases from decisions of federal regulatory agencies as well.

Appeals courts have no juries, and panels of judges (usually three) decide the cases. Their decisions are almost always final. Their decisions may be appealed only to the Supreme Court, and because the Court is able to hear only a very small percentage of them, almost no cases go further than the appeals courts.

Thus, even though the Founders surely intended that Congress hold a great deal of power over the judicial branch, in reality the basic organization of federal courts has remained basically the same throughout U.S. history. Congress has created new courts and reorganized others, and the system has grown increasingly complex. The courts have a great deal of independence, however, and they have established the judicial branch as a strong coequal to Congress and the president.