Steven Girard: Part 2

Merchant, Mariner, Banker, Philanthropist, Humanitarian, Patriot

by Mike DiMeo, Girard College graduate (1939) and author of "The Stone Cocoon," about the college.

Girard Disagrees with Washington

There was great unrest on the oceans of the world as the glow of victory over the dreaded Yellow Fever subsided for Girard and the year 1793 ran its course. His shipping enterprises were at risk again as marauding vessels, including British warships, French and Spanish privateers, seized many of his ships, and confiscated his cargoes. In the years between 1793 and 1795, Girard initiated a movement to have the U.S. government be more heavily involved in protecting the shipping industry. There was war between France and Great Britain at that time, and Girard was in sharp disagreement with President Washington's foreign policy on that issue. It was his contention that the United States should be more supportive of France. He reasoned that France had come to the aid of the young republic in its struggle to gain independence; it was then quite proper for the United States to reciprocate, he further would suggest. In giving aid to the French, at the same time, the United States warships could provide security for all shipping. That was Girard's reasoning.

There was little of substance that came from his verbal confrontation with the Washington administration. A treaty was effected with Britain but gave little promise that the British would halt their aggressive actions against shipping. In fact, the compromise known as the "Jay Treaty," (John Jay was Washington's envoy to Britain) was quite conciliatory to the British and satisfied few, Girard being one of the most vocal in arguing its decidedly favorable British concessions. President Washington also saw the treaty as a victory in diplomatic circles for the British and a stinging setback for young America. But the president reasoned that it was a necessity for the time.

Despite the uncertainties of shipping worldwide, Girard's business enterprises continued to prosper; his wealth increased accordingly, but he remained a simple man, luxuriating only in a penchant for good food, fine wine and his mistress. As he approached the middle years of his life, he seemed to more enjoy his work and the increased demands made on him physically and emotionally. He shared his increased wealth willingly with those around him, giving considerable sums to charity, and afforded care and consideration for those whom he employed.

Idle Hands...

Generosity was one side of Girard that was apparent; another equally obvious characteristic was his discontent with an idle man; he found idleness to be offensive. One of those who benefited most by his generosity was the brother of his mistress, Sally Bickham. Girard had taken her younger brother into his care many years earlier. Martin Bickham gained much from Girard's love and teaching; he was treated as the son Stephen Girard never had. With Girard as his mentor and protector, Martin was introduced to the business world when only fourteen years of age. Under Girard's tutelage, Sally Bickham watched with pride as her brother became a eager student, absorbing the business savvy that his benefactor so willingly put before him, and prospered as a lifetime employee. With Sally and her brother under the same roof, Girard lived the family life he seemed to enjoy.

Mistress #2

In 1796, that family atmosphere was markedly changed. Sally Bickham, Girard's surrogate wife for nine years, left his side to marry. The parting was amicable and Girard was sorry to see her leave, but he did not tarry long in replacing Sally. Shortly after her departure, Girard took another mistress. Polly Kenton, a laundress, twenty-six years younger than Girard, and only twenty-six years of age, moved into the Girard house.

Girard's worth at that time was in excess of $250,000, and he was well on his way to becoming a millionaire; Polly Kenton saw that as incentive to take on the role as mistress. She did not disappoint Girard, giving him all the comforts that such a relationship included. In return, Girard lavished upon her gifts of extreme extravagance, a contradiction to the austerity he normally exhibited, especially in business matters. But Polly was a woman cut from the same cloth as Girard; she worked hard and expected others to do the same. Aside from his love for her, Girard wanted to honor his mistress with gifts that would please her as a woman.

Down on the Farm

In addition to his wealth-building expertise in shipping and shipbuilding and in sharp contrast to the environment of the maritime business, Girard purchased a farm at the southern end of Philadelphia. He used the land as a working farm on which he would do much of the manual labor. His daily regimen included visits to the farm; it was a pleasant removal from his normal business of ships and other maritime matters. He loved the feel of the soil and the hard work associated with farming. Included with the purchase of the farm was a farmhouse that still stands today at Twenty-First and Shunk Streets. Girard never lived in that farmhouse, but those in his employ who did live there were ever conscious of his presence on the farm each day.

Many of the hundreds of fortunate youngsters who attended Girard College, a school Girard later endowed, and who gained so much through the excellence that Girard College represents, regularly gather at the farmhouse in ceremonies to honor their benefactor.

The angst that Girard suffered when the Jay Treaty was approved by the Washington administrations years earlier was relieved when Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801. Girard worked on Jefferson's behalf toward his election and was rewarded when Jefferson made drastic changes in foreign policy, changes that Girard had wanted and was denied by the Jay Treaty. Jefferson also took other measures to gain safety for ships at sea from which Girard took pleasure and comfort. Jefferson was Girard's kind of president.

The nineteenth century began with continuing unrest; the war between France and Great Britain still made trading with European nations a risky business. Stephen Girard began to look more to longer trade routes that could be profitable while he lessened his attention somewhat to those that were closer by in Europe. He eyed especially, the possibilities of increasing his trade with China. The shipping lanes to that distant land sent Girard's vessels around South America, and made ports along the way attractive for trade as well.

A Revolutionary Experience

He had been secretly selling arms to revolutionaries in South America, Simon Bolivar, in particular. Other South American countries also were experiencing political upheaval. It was a time for bold and perhaps risky moves toward supplying those countries with not only the implements of war, but also with everyday necessities.

Girard was not one to shy away from risk if profit came from that risk. He did not plunge into unwarranted trouble sites, but weighed carefully his return. He tactfully petitioned the federal government, President Madison in particular, to approve his desire to supply those countries in South America, fighting to maintain their independence, with arms and supplies. Girard got no approval; in fact, he received no response at all from President Madison. Girard, therefore, drew the conclusion that he could not and should not supply the South American rebels with arms and ammunition.

The problems with Great Britain had not abated and, in fact, the War of 1812 was on the horizon. In 1811, Girard was sixty-one years of age and had become a multi-millionaire, the richest man in America. His ability to continue to build his fortune was always at risk, however; piracy on the high seas still persisted, threatening ships and cargoes. Girard constantly reminded his government about what he felt was their responsibility to offer protection. Diplomatic and political effort failed to resolve the hardening impasse between the British and the Americans. Each took reprisals aimed at stifling trade between them, each banning one country's imports from the other.

Girard's Bank

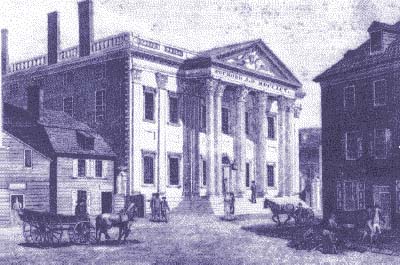

Earlier, in 1791, Congress had sanctioned a national bank; the First Bank of the United States was born and began operations later that year. The public was permitted to buy shares in the fledgling enterprise. Stephen Girard, ever on the prowl for newer ways to turn a profit, intuitive in his assessment of opportunity, invested heavily and by 1811 was the bank's largest shareholder.

In 1812, the Bank's charter was due for renewal. There was great debate on the merits of government in banking; Girard was one who saw benefit in government operating a bank. The charter was not renewed however as the congress defeated the motion to renew. The Bank's property was put up for sale, and Girard, the opportunist, bought the Bank and its assets, reopening the facility almost immediately. Thus, this highly successful shipping magnate and merchant of high repute and skill boldly stepped into another business venture that would bring him enormous profit, far beyond even his boldest estimates. He was farsighted and he was fearless. Becoming a banker was only another conquest for this shrewd, hard-working man. Girard became a banker almost overnight and, in the process, he became America's most powerful banker. In naming his bank simply, Girard's Bank, it was not done to vent his ego. Rather, it exemplified his simple, straightforward, personality. There was no need for grandeur and pomposity. Girard's Bank would figure prominently in the future of his adopted nation in short order.

War of 1812

On June 18, 1812, after exhaustive and repeated attempts to solve the differences between America and Great Britain that had festered over the years, President Madison signed an official declaration of war against the nation the United States had defeated three decades earlier in the Revolutionary War.

There was determination in the declaration of war, but there was also great risk. America was hardly capable of conducting the war with any superiority in numbers or equipment. As a fledgling nation, only beginning to gather itself as an independent, America was hardly in a position to conduct a war. It would need resources and money. On the opposite side, the British were in a far better position to conduct a successful war.

After many attempts to shore up the finances of the Treasury Department, all of them failing, it became obvious to all government officials and Stephen Girard, that the United States would lose the war with the British unless a large infusion of money was made to the U.S. Treasury. In early 1813, the fears became fact: the U. S. Treasury had run out of money. Stephen Girard was the only one with the necessary cash to make the Treasury solvent once more. John Jacob Astor and a few other lesser financiers had committed to a part of the sum needed to help the Treasury, but their commitment fell far short of the sum needed to finance the war.