The Slave Quarters

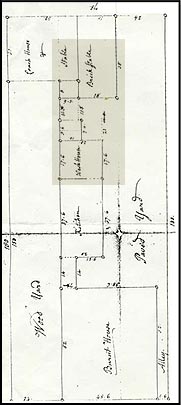

1785 map overlaid with the Liberty Bell Center footprint (blue). The smokehouse and its addition are shown in red. 2002 National Park Service map, with additions by Ed Lawler.

by Edward Lawler, Jr.

Visitors heading to the Liberty Bell will walk upon the site of the Slave Quarters of the President's House as they approach the main entrance to the Liberty Bell Center. This fact should not be hidden from them. Independence National Historical Park has an obligation to interpret the Slave Quarters along with the rest of the President's House.

Plans for the President's House site were unveiled at a public meeting on January 15, 2003, with no mention of the Slave Quarters. The proposed design includes a full-sized outline in the paving of the main house and kitchen ell, but the outline does not include the Slave Quarters. Slavery is to be interpreted elsewhere on the property, but Independence Park officials have made it clear that they have no intention of interpreting slavery at the actual site of the Slave Quarters, 5 feet from the main entrance to the Liberty Bell Center.

Is "Slave Quarters" the Right Term?

While the term "slave quarters" may bring to mind plantation cabins, its use also is appropriate here. Some of the alterations were planned specifically to accommodate the black stableworkers, and Washington seems to have had every expectation of slaves being housed behind the kitchen ell for the duration of his presidency. He did not anticipate the negative public reaction that his driving through the streets of the city in a coach with black footmen would cause, nor the subversive effect that abolitionist Philadelphia and its free-black community would have on his enslaved Africans. The President replaced the black stableworkers with white German indentured servants, although the earliest record of an indentured servant being hired is not until March 1792. Austin died on December 20, 1794, and all the subsequent stableworkers seem to have been white.

Proving beyond a shadow of a doubt which of these two tiny rooms housed who, may never be possible. But, in the larger scheme of things, it is not that important. All of the household staff is accounted for in the disposition of rooms in the Washington-Lear correspondence. The President designated the smokehouse and its addition as housing for the stableworkers, most of whom were enslaved. Both rooms should be considered part of the Slave Quarters.

PBS in their "American Experience" website uses the term Urban Slave Quarters to refer to a dwelling for enslaved people in a city environment. In Medford, Massachusetts, The Royall House and Slave Quarters is an example of the term applied to a northern historic site.

Construction

"Richd Penn's Burnt House Lot — Philadelphia." Unknown draftsman, ca. 1785. RG-17 Land Office Map Collection, Pennsylvania State Archives. The shaded area is seen enlarged below.

In a series of letters written between September 5 and October 31, 1790, Washington and his chief secretary, Tobias Lear, discussed the alterations to the house necessary to accommodate the President, his wife, and her 2 grandchildren; the office staff of 4, and Lear's wife; 15 or 16 white servants; and the 8 enslaved Africans from Mount Vernon.

The terms white "servants" and black "slaves" are used here to avoid any misunderstanding about the legal status of the workers in the President's House. Through much of the 20th century, the use of the euphemism "servants" for both whites and blacks led to the erroneous assumption that the blacks in Washington's presidential household had been free. This was not so. All eight blacks were enslaved.

Washington's final plans called for Moll and Oney to be housed in a divided room over the kitchen with the grandchildren; for 3 of the black men to be housed in a divided room in the attic (separate from the white men); and for the white coachman, Arthur Dunn, and the black stableworkers, Giles, Paris, and probably Austin, to be housed behind the kitchen ell. In an October 31, 1790 letter, Lear confirmed the President's order: "The Smoke-House will be extended to the end of the Stable, and two good rooms made in it for the accomodation [sic] of the Stable people."

The "Smoke-House" is clearly visible on the 1785 map of the property, attached to the south wall of the "Wash House." Assuming the typical 9-inch brick walls (2 bricks thick), its interior would have been about 8-1/2 feet square. The "Cow House" is the rectangle attached to the "Coach House & Stable" and the "Brick Stable." Washington ordered the cow house converted into additional stalls for his horses. Between the smokehouse and the cow house is an open shed — three walls and a dotted line indicating a roof. The preponderence of the evidence indicates that Washington's order was carried out, and that this structure was converted into the second room for the "Stable people" by the addition of a single wall and floor. Contary to Independence National Historical Park's public statements (since, recanted in private), there is no evidence of the stable slaves having been housed in the Servants Hall.

Segregation

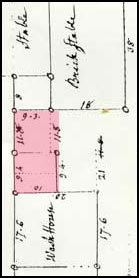

Detail of the 1785 map above, highlighting the location of the smokehouse and its addition.

Why two rooms? The coachman may have been accorded enough status in the household to merit his own room, as were the steward and the butler/valet. There is also the possibility that white servants refused to sleep in the same room with black slaves, or that Washington did not think it proper for them to do so. According to the journal of the French legal scholar Moreau de St. Méry (living in exile in Philadelphia, 1794-98), "A white servant, no matter who, would consider it a dishonor to eat with [free] colored people." The prejudice against enslaved blacks may have been even stronger.

The dividing of the attic room to separate the white and black men strongly indicates racial segregation within the presidential household. In other Philadelphia mansions, the (white) male servants of similar status slept dormitory-style in a single room. Segregation also may have extended to the stableworkers. Assuming a 9-inch brick wall continuing the west wall of the smokehouse to the stable, the addition Washington ordered built would have had an interior of about 8-1/2 by 11-1/2 feet. It is likely that the white coachman occupied the smokehouse, and the black stableworkers, the larger addition. It is also possible that it was the other way around. The racial segregation practiced elsewhere in the house (and at Mount Vernon) and the hierarchy of the household staff make the possibility of the white coachman and a black stableworker having shared one of these rooms extremely remote.

The Importance of Marking the Slave Quarters

Why is it necessary to mark the slave quarters? It is necessary to mark them because of the overwhelming power of "place." That a personal connection or bond is forged by inhabiting the same space as someone who preceded you, or standing exactly where something occurred. No matter how much one understands a thing abstractly, the confirmation of one's senses is needed to truly make something real. The term "Doubting Thomas" comes from the New Testament. He was the disciple who couldn't believe his eyes and ears, but had to touch the wounds of the resurrected Christ. For many of us, the need is to make it real that fellow human beings were owned and woefully exploited, and, in the case of the President's House, that it took place exactly here.

The shining perfection of the promises made in America's founding documents often blinds us to the flaws, compromises, and betrayals contained in them. The iconic status of Washington as the embodiment of the nation-in-the-making, or of the Liberty Bell as the emblem of self-government and self-expression has less to do with reality than with a longing for an ideal. Unfortunately, there never was an idealized past; the past was as messy and complex as the present. Whether the Founders were great men is openly debated by scholars; that great things were accomplished is undeniable.

If the proposed design for the President's House site is built, future visitors to Independence Mall will travel from the main house and an extensive interpretation of Washington and Adams, walk through a "slave" area with artwork and text interpreting the experience of Africans in America, then enter the new Liberty Bell Center for a comprehensive interpretation of the bell (including its use as the symbol of the abolitionist movement), concluding at the other end of the LBC with an encounter with the bell itself. Marking the Slave Quarters in the paving with the rest of the house will enhance, rather than diminish the effect of this journey.

Slavery is permanently stamped on this tiny piece of real estate. That fact should not be hidden or minimized, but acknowledged and embraced. We all have a need to touch the wound before we can understand. And from understanding, comes healing.