11d. Bunker Hill

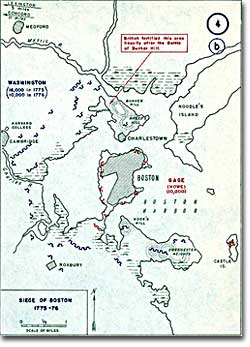

This map shows details of the 1775-76 siege of Boston and outlines Bunker Hill and Breed's Hill on the Charlestown Peninsula.

On the night of June 16, 1775, a detail of American troops acting under orders from Artemas Ward moved out of their camp, carrying picks, shovels, and guns. They entrenched themselves on a rise located on Charleston Peninsula overlooking Boston. Their destination: Bunker Hill.

From this hill, the rebels could bombard the town and British ships in Boston Harbor. But Ward's men misunderstood his orders. They went to Breed's Hill by mistake and entrenched themselves there — closer to the British position.

Cannon for Breakfast

The next morning, the British were stunned to see Americans threatening them. In the 18th century, British military custom demanded that the British attack the Americans, even though the Americans were in a superior position militarily (the Americans had soldiers and cannon pointing down on the British).

William Howe was the commander in chief of the British army at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Major General William Howe, leading the British forces, could have easily surrounded the Americans with his ships at sea, but instead chose to march his troops uphill. Howe might have believed that the Americans would retreat in the face of a smashing, head-on attack.

He was wrong.

His Majesty's ships opened fire on the Americans. Early in the afternoon, 28 barges of British soldiers crossed the Charles River and stormed the hills. The Americans waited until the British were within 15 paces, and then unleashed a bloody fusillade. Scores of British troops were killed or wounded; the rest retreated down the hill.

Again, the British rushed the hill in a second wave. And again they retreated, suffering a great number of casualties.

By the time the third wave of British charged the hill, the Americans were running low on ammunition. Hand-to-hand fighting ensued. The British eventually took the hill, but at a great cost. Of the 2,300 British soldiers who had gone through the ordeal, 1,054 were either killed or wounded.

|

Dear and Hon'd Mother ... Friday the 16 of June we were orderd on parade at six 'o Clock, with one days provision and Blankets ready for a March somewhere, but we knew not where but we readily and cheerfully obey'd, ... [W]e march'd down, on to Charleston Hill against Copts hill in Boston, where we entrench'd & made a Fort ... we work'd there undiscovered till about five in the Morning, when we saw our danger, being against Ships of the Line, and all Boston fortified against us, The danger we were in made us think there was treachery and that we were brought there to be all slain, and I must and will say that there was treachery oversight or presumption in the Conduct of our Officers, for about 5 in the morning, we not having more than half our fort done, they began to fire (I suppose as soon as they had orders) pretty briskly for a few minutes, then ceas'd but soon begun again, and fird to the number of twenty minutes, (they killd but one of our Men) then ceas'd to fire till about eleven oClock when they began to fire as brisk as ever, which caus'd many of our young Country people to desert, apprehending the danger in a clearer manner than others who were more diligent in digging, & fortifying ourselves against them. – Peter Brown, letter to his mother (June 25, 1775) Massachusetts Historical Society | ||

On July, 2, 1775, George Washington rode into Cambridge, Massachusetts, to take command of the new American army. He had a formidable task ahead of him. He needed to establish a chain of command and determine a course of action for a war — if there would be a war.

Why Washington

Washington was one of the few Americans of the era to have military experience. He had served with distinction in the French and Indian War.

Washington was also a southerner. Politicians from the north (such as John Adams) recognized that, for the Americans to have any shot at defeating the British, all regions of the country would have to be involved. The uprising had to be more than just New England agitation.

In London, the news of Bunker Hill convinced the king that the situation in the Colonies had escalated into an organized uprising and must be treated as a foreign war. Accordingly, he issued a Proclamation of Rebellion.

This Means War

British general William Howe ordered his troops to cross the Charles River and attack the American troops atop Bunker Hill.

The British had taken the initiative, but they, like Washington, needed to establish a plan of action. How did they plan to win the war? With the help of loyal colonials! "There are many inhabitants in every province well affected to Government, from whom no doubt we shall have assistance," General Howe wrote. But he hedged: the Loyalists could not rally "until His Majesty's armies have a clear superiority by a decisive victory."

The general needed a showdown. But first he needed supplies, reinforcements, and a scheme to suppress the rebels. Almost 11 months after the shots at Bunker Hill were fired, Howe departed Boston and moved north to Nova Scotia to wait and plan.

He did win decisive victories later, but his assumption that the Loyalists would rally behind him was simply wrong.