11g. The Battle of Saratoga

British general John Burgoyne earned the nickname "Gentleman Johnny" for his love of leisure and his tendency to throw parties between battles. His surrender to American forces at the Battle of Saratoga marked a turning point in the Revolutionary War.

The Battle of Saratoga was the turning point of the Revolutionary War.

The scope of the victory is made clear by a few key facts: On October 17, 1777, 5,895 British and Hessian troops surrendered their arms. General John Burgoyne had lost 86 percent of his expeditionary force that had triumphantly marched into New York from Canada in the early summer of 1777.

Divide and Conquer

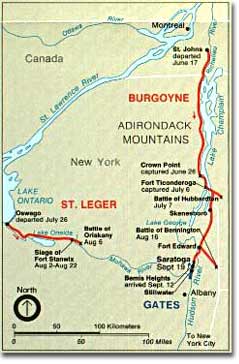

The divide-and-conquer strategy that Burgoyne presented to British ministers in London was to invade America from Canada by advancing down the Hudson Valley to Albany. There, he would be joined by other British troops under the command of Sir William Howe. Howe would be bringing his troops north from New Jersey and New York City.

Burgoyne believed that this bold stroke would not only isolate New England from the other American colonies, but achieve command of the Hudson River and demoralize Americans and their would-be allies, such as the French.

Some historians today are unsure if her death came at Native American hands or by other means, but the murder of Jane McCrea united Americans against the British and their Native American allies.

In June 1777, Burgoyne's army of over 7,000 men (half of whom were British troops and the other half Hessian troops from Brunswick and Hesse-Hanau) departed from St. Johns on Lake Champlain, bound for Fort Ticonderoga, at the southern end of the lake.

As the army proceeded southward, Burgoyne drafted and had his men distribute a proclamation that, among other things, included the statement "I have but to give stretch to the Indian forces under my direction, and they amount to thousands," which implied that Britain's enemies would suffer attacks from Native Americans allied to the British.

More than any other act during the campaign, this threat and subsequent widely reported atrocities such as the scalping of Jane McCrea stiffened the resolve of the Americans to do whatever it took to assure that the threat did not become reality.

Instead of heading north to help Burgoyne fight the rebels in Saratoga, General Howe sailed south and embarked on a campaign to capture Philadelphia.

Round One to the British

The American forces at Fort Ticonderoga recognized that once the British mounted artillery on high ground near the fort, Ticonderoga would be indefensible. A retreat from the Fort was ordered, and the Americans floated troops, cannon, and supplies across Lake Champlain to Mount Independence.

From there the army set out for Hubbardton where the British and German troops caught up with them and gave battle. Round one to the British.

Burgoyne continued his march towards Albany, but miles to the south a disturbing event occurred. Sir William Howe decided to attack the Rebel capital at Philadelphia rather than deploying his army to meet up with Burgoyne and cut off New England from the other Colonies. Meanwhile, as Burgoyne marched south, his supply lines from Canada were becoming longer and less reliable.

|

I have the honor to inform your Lordship that the enemy [were] dislodged from Ticonderoga and Mount Independent, on the 6th instant, and were driven on the same day, beyond Skenesborough on the right, and the Humerton [Hubbardton] on the left with the loss of 128 pieces of cannon, all their armed vessels and bateaux, the greatest part of their baggage and ammunition, provision and military stores ... – General John Burgoyne, letter to Lord George Germain (1777) | ||

Bennington: "the compleatest Victory gain'd this War"

As Burgoyne and his troops marched down from Canada, the British managed to win several successful campaigns as well as infuriate the colonists. By the time Burgoyne reached Saratoga, Americans had successfully rallied support to beat him.

In early August, word came that a substantial supply depot at Bennington, Vermont, was alleged to be lightly guarded, and Burgoyne dispatched German troops to take the depot and return with the supplies. This time, however, stiff resistance was encountered, and American general John Stark surrounded and captured almost 500 German soldiers. One observer reported Bennington as "the compleatest Victory gain'd this War."

Burgoyne now realized, too late, that the Loyalists (Tories) who were supposed to have come to his aid by the hundreds had not appeared, and that his Native American allies were also undependable.

American general Schuyler proceed to burn supplies and crops in the line of Burgoyne's advance so that the British were forced to rely on their ever-longer and more and more unreliable supply line to Canada. On the American side, General Horatio Gates arrived in New York to take command of the American forces.

Battle of Freeman's Farm

Mask letters, invisible ink, and secret code are the tricks of the trade for any good spy. Loyalist Henry Clinton used a mask letter to communicate with Burgoyne.

By mid-September, with the fall weather reminding Burgoyne that he could not winter where he was and needed to proceed rapidly toward Albany, the British army crossed the Hudson and headed for Saratoga.

On September 19 the two forces met at Freeman's Farm north of Albany. While the British were left as "masters of the field," they sustained heavy human losses. Years later, American Henry Dearborn expressed the sentiment that "we had something more at stake than fighting for six Pence pr Day."

Battle of Saratoga

In late September and during the first week of October 1777, Gate's American army was positioned between Burgoyne's army and Albany. On October 7, Burgoyne took the offensive. The troops crashed together south of the town of Saratoga, and Burgoyne's army was broken. In mop-up operations 86 percent of Burgoyne's command was captured.

The victory gave new life to the American cause at a critical time. Americans had just suffered a major setback the Battle of the Brandywine along with news of the fall of Philadelphia to the British.

One American soldier declared, "It was a glorious sight to see the haughty Brittons march out & surrender their arms to an army which but a little before they despised and called paltroons."

A stupendous American victory in October 1777, the success at Saratoga gave France the confidence in the American cause to enter the war as an American ally. Later American successes owed a great deal to French aid in the form of financial and military assistance.

A Word about Spies

Spies worked for both British and American armies. Secret messages and battle plans were passed in a variety of creative ways, including being sewn into buttons. Patriots and loyalists penned these secret letters either in code, with invisible ink, or as mask letters.

Here is an example of Loyalist Sir Henry Clinton's mask letter. The first letter is the mask letter with the secret message decoded; the second is an excerpt of the full letter.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold is best remembered as a traitor; an American patriot who spied for the British during the American Revolution. But there is more to his story than this sad event.

Arnold was a fierce patriot during the Stamp Act crisis and the early years of the American Revolution. During the battles of Lexington and Concord, Arnold worked with Ethan Allen to capture Fort Ticonderoga and was named a colonel.

As a member of George Washington's Continental Army, he led a failed attack on Quebec, but was nonetheless named brigadier general in 1776.

His next big moment came at the Battle of Saratoga. Here, Benedict Arnold was instrumental in stopping the advance of the British and in obtaining the surrender of British General John Burgoyne.

During the Battle of Freeman's Farm, Arnold's leg was severely wounded when pinned beneath his horse. (Both Arnold and his leg survived, there is a monument to his leg at Saratoga National Historic Park.)

Over the next two years, Benedict Arnold remained a patriot, but was upset and embittered at what he felt was a lack of his recognition and contribution to the war. In 1778, following British evacuation of Philadelphia, George Washington appointed Arnold military commander of the city.

This is where the story gets interesting.

In Philadelphia, Benedict Arnold was introduced to and fell in love with Margaret (Peggy) Shippen, a young, well-to-do loyalist who was half his age. Ms. Shippen had previously been friendly with John André, a British spy who had been in Philadelphia during the occupation as the adjutant to the British commander in chief, Sir Henry Clinton. It is believed that Peggy introduced Arnold to André.

Meanwhile, Benedict Arnold's reputation while in Philadelphia was beginning to tarnish. He was accused of using public wagons for private profit and of being friendly to Loyalists. Faced with a court-martial for corruption, he resigned his post on March 19, 1779.

Following his resignation, Arnold began a correspondence with John André, now chief of British intelligence services. But Arnold had also maintained his close relationship with George Washington and still had access to important information. Over the next few months Benedict Arnold continued his talks with André and agreed to hand over key information to the British. Specifically, Arnold offered to hand over the most strategic fortress in America: West Point.

Arnold and André finally met in person, and Arnold handed over information to the British spy. But, unfortunately for both men, André was caught and Arnold's letter was found. Arnold's friend, George Washington, was heartbroken over the news, but was forced to deal with the treacherous act. While Benedict Arnold escaped to British-occupied New York, where he was protected from punishment.

John André was executed for spying.

Benedict Arnold was named brigadier general by the British government and sent on raids to Virginia. Following Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown in 1781, Arnold and his family sailed to Britain with his family. He died in London in 1801.