13b. The War Experience: Soldiers, Officers, and Civilians

Before they could fight for independence, harsh winters during the Revolutionary War forced the Continental Army to fight for their very survival.

Americans remember the famous battles of the American Revolution such as Bunker Hill, Saratoga, and Yorktown, in part, because they were Patriot victories. But this apparent string of successes is misleading.

The Patriots lost more battles than they won and, like any war, the Revolution was filled with hard times, loss of life, and suffering. In fact, the Revolution had one of the highest casualty rates of any U.S. war; only the Civil War was bloodier.

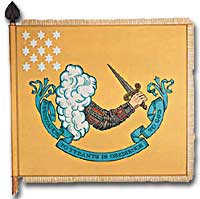

A battle flag carried by Revolutionary War soldiers. The banner reads "Resistance to Tyrants is Obedience to God."

In the early days of 1776, most Americans were naïve when assessing just how difficult the war would be. Great initial enthusiasm led many men to join local militias where they often served under officers of their own choosing. Yet, these volunteer forces were not strong enough to defeat the British Army, which was the most highly trained and best equipped in the world. Furthermore, because most men preferred serving in the militia, the Continental Congress had trouble getting volunteers for General George Washington's Continental Army. This was in part because, the Continental Army demanded longer terms and harsher discipline.

Washington correctly insisted on having a regular army as essential to any chance for victory. After a number of bad militia losses in battle, the Congress gradually developed a stricter military policy. It required each state to provide a larger quota of men, who would serve for longer terms, but who would be compensated by a signing bonus and the promise of free land after the war. This policy aimed to fill the ranks of the Continental Army, but was never fully successful. While the Congress authorized an army of 75,000, at its peak Washington's main force never had more than 18,000 men. The terms of service were such that only men with relatively few other options chose to join the Continental Army.

Part of the difficulty in raising a large and permanent fighting force was that many Americans feared the army as a threat to the liberty of the new republic. The ideals of the Revolution suggested that the militia, made up of local Patriotic volunteers, should be enough to win in a good cause against a corrupt enemy. Beyond this idealistic opposition to the army, there were also more pragmatic difficulties. If a wartime army camped near private homes, they often seized food and personal property. Exacerbating the situation was Congress inability to pay, feed, and equip the army.

When British General John Burgoyne surrendered to the Patriots at Saratoga on October 7, 1777 (illustrated above), colonists believed it would be proof enough to the French that American independence could be won. Benjamin Franklin immediately spread word to Louis XVI in hopes the king would offer support for the cause.

As a result, soldiers often resented civilians whom they saw as not sharing equally in the sacrifices of the Revolution. Several mutinies occurred toward the end of the war, with ordinary soldiers protesting their lack of pay and poor conditions. Not only were soldiers angry, but officers also felt that the country did not treat them well. Patriotic civilians and the Congress expected officers, who were mostly elite gentlemen, to be honorably self-sacrificing in their wartime service. When officers were denied a lifetime pension at the end of the war, some of them threatened to conspire against the Congress. General Washington, however, acted swiftly to halt this threat before it was put into action.

The Continental Army defeated the British, with the crucial help of French financial and military support, but the war ended with very mixed feelings about the usefulness of the army. Not only were civilians and those serving in the military mutually suspicious, but also even within the army soldiers and officers could harbor deep grudges against one another. The war against the British ended with the Patriot military victory at Yorktown in 1781. However, the meaning and consequences of the Revolution had not yet been decided.