14b. Articles of Confederation

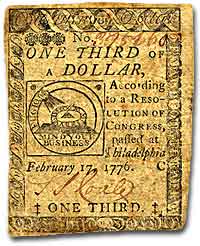

The paper money issued by the Continental Congress was known as "Continentals." Not backed by silver or gold, the currency did not retain its value, and the saying "not worth a Continental" took root.

While the state constitutions were being created, the Continental Congress continued to meet as a general political body. Despite being the central government, it was a loose confederation and most significant power was held by the individual states. By 1777 members of Congress realized that they should have some clearly written rules for how they were organized. As a result the Articles of Confederation were drafted and passed by the Congress in November.

This first national "constitution" for the United States was not particularly innovative, and mostly put into written form how the Congress had operated since 1775.

Even though the Articles were rather modest in their proposals, they would not be ratified by all the states until 1781. Even this was accomplished largely because the dangers of war demanded greater cooperation.

The purpose of the central government was clearly stated in the Articles. The Congress had control over diplomacy, printing money, resolving controversies between different states, and, most importantly, coordinating the war effort. The most important action of the Continental Congress was probably the creation and maintenance of the Continental Army. Even in this area, however, the central government's power was quite limited. While Congress could call on states to contribute specific resources and numbers of men for the army, it was not allowed to force states to obey the central government's request for aid.

Revolutions need strong leaders and willing citizens to succeed, but they also need money. By curbing inflation and stabilizing the early economy, Robert Morris helped ensure the success of the American Revolution.

The organization of Congress itself demonstrates the primacy of state power. Each state had one vote. Nine out of thirteen states had to support a law for it to be enacted. Furthermore, any changes to the Articles themselves would require unanimous agreement. In the one-state, one-vote rule, state sovereignty was given a primary place even within the national government. Furthermore, the whole national government consisted entirely of the unicameral (one body) Congress with no executive and no judicial organizations.

The national Congress' limited power was especially clear when it came to money issues. Not surprisingly, given that the Revolution's causes had centered on opposition to unfair taxes, the central government had no power to raise its own revenues through taxation. All it could do was request that the states give it the money necessary to run the government and wage the war. By 1780, with the outcome of the war still very much undecided, the central government had run out of money and was bankrupt! As a result the paper money it issued was basically worthless.

Robert Morris, who became the Congress' superintendent of finance in 1781, forged a solution to this dire dilemma. Morris expanded existing government power and secured special privileges for the Bank of North America in an attempt to stabilize the value of the paper money issued by the Congress. His actions went beyond the limited powers granted to the national government by the Articles of Confederation, but he succeeded in limiting runaway inflation and resurrecting the fiscal stability of the national government.