23e. John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams, the 6th President of the U.S., was also the defense attorney in the famous case of the slave rebellion on the Amistad.

Like his father who was also a one-term president, John Quincy Adams was an intelligent statesman whose strong commitment to certain principles proved to be liabilities as president.

For instance, Adams favored a bold economic role for the national government that was far ahead of public opinion. Like the Democratic-Republicans who preceded him in the Era of Good Feelings, Adams supported a federal role in economic development through the American System that was chiefly associated with Henry Clay. Adams' vision of federal leadership was especially creative and included proposals for a publicly-funded national university and government investment in scientific research and exploration.

John Adams' wife Louisa was born outside of the United States. Adams' political enemies used this as fodder to accuse him of being pro-British.

Few of Adams' ideas were put into action. He hurt his own case by publicly expressing concerns about the potential dangers of democracy. When politicians in Congress refused to act decisively for fear of displeasing the voters, Adams chided them that they seemed to "proclaim to the world that we are palsied by the will of our constituents."

Although he astutely identified a problem faced by leaders in a democracy, to many Americans he seemed to call into question a central tenet of the new nation. In many respects Adams was a figure of an earlier political era.

For example, he steadfastly refused to campaign for his own re-election because he felt that political office should be a matter of service and not a popularity contest. Although his ideals were surely honorable, when he said that, "if the country wants my services, she must ask for them," he appeared to be an elitist who disdained contact with ordinary people.

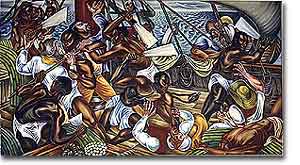

In Mutiny, Hale Woodruff captures the terrifying and heroic moment when enslaved Africans aboard the Amistad launch a rebellion against their captors.

John Quincy Adams' public dedication to unpopular principles helped assure his defeat in the presidential election of 1828. They also led him to take on causes that today seem impressive. For example, Adams overturned a treaty signed by the Creek nation in 1825 that ceded its remaining land to the state of Georgia because he believed that it had been fraudulently obtained through coercive methods. Georgia's governor was outraged, but Adams believed that the matter clearly fell under federal jurisdiction. Although Adams' support of the Creeks didn't prevent their removal to the west, he lost political backing from Americans who widely believed that whites deserved access to all Indian lands.

Adams continued this course of following principle rather than popularity when he served in the U.S. House of Representatives after his presidency. Although not a radical opponent of slavery himself, he was an early leader against congressional rules that prevented anti-slavery petitions from being presented to Congress. He also successfully defended enslaved Africans before the U.S. Supreme Court in the celebrated Amistad case.