26. An Explosion of New Thought

American artists developed a style completely different from their European counterparts in the early 1800s. Reflective of the new American character, artists of the Hudson River School emphasized the natural beauty of the frontier.

What did it mean to think like an American? Once the colonists had thrown off the burdens and controls of England, the possibilities for political, social and artistic creativity and experimentation seemed limitless. People felt optimistic and determined that a new order would be brought to bear, not just on government but on all institutions of social interaction. So, from the beginning of the 1800s until the first gunshot of the Civil War, the American experiment unfolded like an epic. Opportunity, heightened by political freedom and a surge of nationalism, caused most citizens to believe that the experiment might actually work. Thus, a uniquely American tradition in literature, art, thought, and social reform emerged.

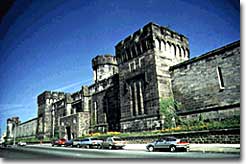

Prisons like Eastern State Penitentiary were intended to help criminals reform their ways rather than just to punish them.

Religion was renewed through a Second Great Awakening. Evangelists on a "divine mission" believed that churches were the proper agents of change, not violence or political movements. Ardent believers in the perfectibility of society tried communal living with distinctly utopian goals, convinced that ultimately their small fellowships would grow into larger, more influential gatherings for the common good of all. Women began to explore the possibility of individual rights and equality with men. Their agenda was quite vast and included not only the right to vote but also such diverse problems as prohibition and world peace. Reformers, sure that the dire human conditions in prisons, workhouses and asylums were the result of bad institutions and not bad people, made gallant efforts to alleviate pain and suffering. Hopes were high that cures for social disorders in America caused by rapid expansion, population growth, and industrialization would work.

Walden Pond was the inspiration for Henry David Thoreau's transcendentalist musings.

In addition, a new school of artists sought to depict a love of nature and the feeling for our place in it by painting the grandeur and panorama of an unspoiled American landscape. And the new American thinkers? They exhorted each citizen to "Hitch your wagon to a star!" The Transcendentalists and literary lights wanted to remind everyone who he or she was and might become. Their philosophy celebrated individualism, the goodness of humankind and the benevolence of the universe.

It was an exciting era to live in. But, like any other, it inevitably developed problems for which neither optimism nor expansion, religion nor reform could provide answers. The tragic flaw in the American experiment would slowly reveal itself in the widening breach between the North and the South over the issue of slavery. As the tone of the Abolitionist cause became more and more shrill, it began to drown out moderation, compromise and good feelings. Americans had previously been willing to argue about everything from women's rights to the virtues of homemade bread, yet rarely did they lose sight of another American's right to disagree. But the unprecedented divisiveness of the institution of slavery and the resultant catastrophe of the Civil War brought down the curtain, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, on "the better angels of our Nature."