27d. Free(?) African-Americans

When Americans think of African-Americans in the Deep South before the Civil War, the first image that invariably comes to mind is one of slavery. However, many African-Americans were able to secure their freedom and live in a state of semi-freedom even before slavery was abolished by war. Free blacks lived in all parts of the United States, but the majority lived amid slavery in the American South. According to the 1860 U.S. Census, there were 250,787 free blacks living in the South in contrast to 225,961 free blacks living everywhere else in the country including the Midwest and the Far West; however, not everyone, particularly free blacks, were captured by census takers. In the upper south, the largest population of free blacks were in Maryland and Virginia; in the mid-Atlantic, the largest population of free blacks was in Philadelphia.

How did African-Americans become free? Some slaves bought their own freedom from their owners, but this process became more and more rare as the 1800s progressed. Many slaves became free through manumission, the voluntary emancipation of a slave by a slaveowner. Manumission was sometimes offered because slaves had outlived their usefulness or were held in special favor by their masters. The offspring of interracial relations were often set free. Some slaves were set free by their masters as the abolitionist movement grew. Occasionally slaves were freed during the master's lifetime, and more often through the master's will. Many African-Americans freed themselves through escape. A few Americans of African descent came to the United States as immigrants, especially common in the New Orleans area.

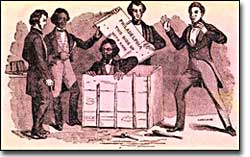

Slaves found many ways to escape to freedom. Henry Box Brown had himself mailed to an abolitionist in Pennsylvania. He went on to become a famous anti-slavery speaker.

Were free blacks offered the same rights as free whites? The answer is quite simply no. For example, a Virginia law, passed in the early 1830s, prohibited the teaching of all blacks to read or write. Free blacks throughout the South were banned from possessing firearms, or preaching the Bible. Later laws even prohibited Negroes who went out of state to get an education from returning. In many states, the slave codes that were designed to keep African-Americans in bondage were also applied to free persons of color. Most horrifically, free blacks could not testify in court. If a slave catcher claimed that a free African-American was a slave, the accused could not defend himself in court.

The African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded despite protests from the white church from which its congregation came.

The church often played a central role in the community of free blacks. The establishment of the African Methodist Episcopal Church represents an important shift. It was established with black leadership and spread from Philadelphia to Charleston and to many other areas in the South, despite laws which forbade blacks from preaching. The church suffered brutalities and massive arrests of its membership, clearly an indication of the fear of black solidarity. Many of these leaders became diehard abolitionists.

Free blacks were highly skilled as artisans, business people, educators, writers, planters, musicians, tailors, hairdressers, and cooks. African-American inventors like Thomas L. Jennings, who invented a method for the dry cleaning of clothes, and Henry Blair Glenn Ross, who patented a seed planter, contributed to the advancement of science. Some owned property and kept boarding houses, and some even owned slaves themselves. Prominent among free persons of color of the period are Frederick Douglass, Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and Harriet Tubman.