32b. The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

The 7th and final debate between Senatorial candidates Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas was held on October 15, 1858, in Alton, Illinois. Today bronze statues of Douglas and Lincoln stand to commemorate the event at Lincoln Douglas Square in Alton.

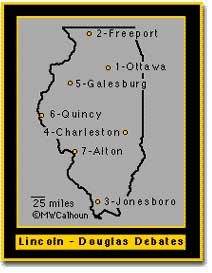

In 1858, as the country moved ever closer to disunion, two politicians from Illinois attracted the attention of a nation. From August 21 until October 15, Stephen Douglas battled Abraham Lincoln in face to face debates around the state. The prize they sought was a seat in the Senate. Lincoln challenged Douglas to a war of ideas. Douglas took the challenge. The debates were to be held at 7 locations throughout Illinois. The fight was on and the nation was watching.

The spectators came from all over Illinois and nearby states by train, by canal-boat, by wagon, by buggy, and on horseback. They briefly swelled the populations of the towns that hosted the debates. The audiences participated by shouting questions, cheering the participants as if they were prizefighters, applauding and laughing. The debates attracted tens of thousands of voters and newspaper reporters from across the nation.

During the debates, Douglas still advocated "popular sovereignty," which maintained the right of the citizens of a territory to permit or prohibit slavery. It was, he said, a sacred right of self-government. Lincoln pointed out that Douglas's position directly challenged the Dred Scott decision, which decreed that the citizens of a territory had no such power.

C-Span sponsored a re-enactment of the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1994.

In what became known as the Freeport Doctrine, Douglas replied that whatever the Supreme Court decided was not as important as the actions of the citizens. If a territory refused to have slavery, no laws, no Supreme Court ruling, would force them to permit it. This sentiment would be taken as betrayal to many southern Democrats and would come back to haunt Douglas in his bid to become President in the election of 1860.

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas met at each of Illinois' 7 Congressional districts for the debates which preceded the election for U.S. Senator in 1858.

Time and time again, Lincoln made that point that "a house divided could not stand." Douglas refuted this by noting that the founders, "left each state perfectly free to do as it pleased on the subject." Lincoln felt that blacks were entitled to the rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, which include "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." Douglas argued that the founders intended no such inclusion for blacks.

Neither Abraham Lincoln nor Stephen Douglas won a popular election that fall. Under rules governing Senate elections, voters cast their ballots for local legislators, who then choose a Senator. The Democrats won a majority of district contests and returned Douglas to Washington. But the nation saw a rising star in the defeated Lincoln. The entire drama that unfolded in Illinois would be played on the national stage only two years later with the highest of all possible stakes.