34a. The Emancipation Proclamation

Americans tend to think of the Civil War as being fought to end slavery. Even one full year into the Civil War, the elimination of slavery was not a key objective of the North. Despite a vocal Abolitionist movement in the North, many people and many soldiers, in particular, opposed slavery, but did not favor emancipation. They expected slavery to die on its own over time.

Click here for the full text of the Emancipation Proclamation

African Americans across the nation celebrated the Emancipation Proclamation. This image shows a Union soldier reading the Proclamation to a slave household.

By mid-1862 Lincoln had come to believe in the need to end slavery. Besides his disdain for the institution, he simply felt that the South could not come back into the Union after trying to destroy it. The opposition Democratic Party threatened to turn itself into an antiwar party. Lincoln's military commander, General George McClellan, was vehemently against emancipation. Many Republicans who backed policies that forbid black settlement in their states were against granting blacks additional rights. When Lincoln indicated he wanted to issue a proclamation of freedom to his cabinet in mid-1862, they convinced him he had to wait until the Union achieved a significant military success.

Slaves in the border states that remained in the Union, shown in dark brown, were excluded from the Emancipation Proclamation, as were slaves in the Confederate areas already held by Union forces (shown in yellow).

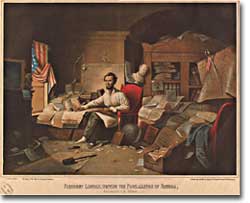

David Blythe imagined a scene like this when he painted President Lincoln Writing the Proclamation of Freedom, January 1, 1863. Note the symbolism in this print, including the flag, the Bible under Lincoln's hand, the Constitution in his lap, the railsplitter at his feet, and the scales of justice in the corner.

That victory came in September at Antietam. No foreign country wants to ally with a potential losing power. By achieving victory, the Union demonstrated to the British that the South may lose. As a result, the British did not recognize the Confederate States of America, and Antietam became one of the war's most important diplomatic battles, as well as one of the bloodiest. Five days after the battle, Lincoln decided to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, effective January 1, 1863. Unless the Confederate States returned to the Union by that day, he proclaimed their slaves "shall be then, thenceforward and forever free."

It is sometimes said that the Emancipation Proclamation freed no slaves. In a way, this is true. The proclamation would only apply to the Confederate States, as an act to seize enemy resources. By freeing slaves in the Confederacy, Lincoln was actually freeing people he did not directly control. The way he explained the Proclamation made it acceptable to much of the Union army. He emphasized emancipation as a way to shorten the war by taking Southern resources and hence reducing Confederate strength. Even McClellan supported the policy as a soldier. Lincoln made no such offer of freedom to the border states.

The Emancipation Proclamation created a climate where the doom of slavery was seen as one of the major objectives of the war. Overseas, the North now seemed to have the greatest moral cause. Even if a foreign government wanted to intervene on behalf of the South, its population might object. The Proclamation itself freed very few slaves, but it was the death knell for slavery in the United States. Eventually, the Emancipation Proclamation led to the proposal and ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which formally abolished slavery throughout the land.