34c. The Northern Homefront

At age 12, with $100 in borrowed money, "Commodore" Cornelius Vanderbilt began building a shipping and railroad empire. He died the richest man in America.

After initial setbacks, most Northern civilians experienced an explosion of wartime production.

During the war, coal and iron production reached their highest levels. Merchant ship tonnage peaked. Traffic on the railroads and the Erie Canal rose over 50%.

Union manufacturers grew so profitable that many companies doubled or tripled their dividends to stockholders. The newly rich built lavish homes and spent their money extravagantly on carriages, silk clothing and jewelry. There was a great deal of public outrage that such conduct was unbecoming or even immoral in time of war. What made this lifestyle even more offensive was that workers' salaries shrank in real terms due to inflation. The price of beef, rice and sugar doubled from their pre-war levels, yet salaries rose only half as fast as prices — while companies of all kinds made record profits.

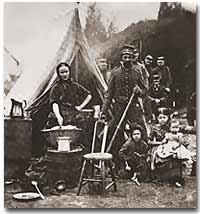

The U.S. Army's regulations allowed four laundresses in each camp, although men did their own laundry in the field. Sometimes soldiers' wives performed this duty for their husbands' regiments.

Women's roles changed dramatically during the war. Before the war, women of the North already had been prominent in a number of industries, including textiles, clothing and shoe-making. With the conflict, there were great increases in employment of women in occupations ranging from government civil service to agricultural field work. As men entered the Union army, women's proportion of the manufacturing work force went from one-fourth to one-third. At home, women organized over one thousand soldiers' aid societies, rolled bandages for use in hospitals and raised millions of dollars to aid injured troops.

Nowhere was their impact felt greater than in field hospitals close to the front. Dorothea Dix, who led the effort to provide state hospitals for the mentally ill, was named the first superintendent of women nurses and set rigid guidelines. Clara Barton, working in a patent office, became one of the most admired nurses during the war and, as a result of her experiences, formed the American Red Cross.

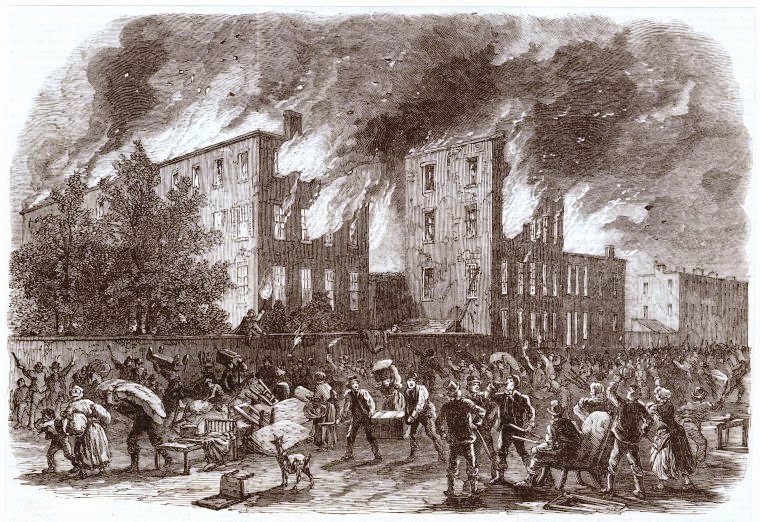

Rioters in New York often targeted African Americans. This scene from a contemporary newspaper shows rioters burning down the African American orphanage.

Resentment of the draft was another divisive issue. In the middle of 1862, Lincoln called for 300,000 volunteer soldiers. Each state was given a quota, and if it could not meet the quota, it had no recourse but to draft men into the state militia. Resistance was so great in some parts of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin and Indiana that the army had to send in troops to keep order. Tempers flared further over the provision that allowed exemptions for those who could afford to hire a substitute.

In 1863, facing a serious loss of manpower through casualties and expiration of enlistments, Congress authorized the government to enforce conscription, resulting in riots in several states. In July 1863, when draft offices were established in New York to bring new Irish workers into the military, mobs formed to resist. At least 74 people were killed over three days. The same troops that had just triumphantly defeated Lee at Gettysburg were deployed to maintain order in New York City.