38a. The Glamour of American Cities

They spread like wildfire. For a new factory to beat the competition, it had to be built quickly. Laborers needed fast, cheap housing located close to work. Roads would be hastily built to connect the factory with the market. There was no grand design, and consequently, the new American city spread unpredictably. Urban sprawl had begun. But the growing beast brought benefits that raised the standard of living to new heights.

Going Up

As surely as the city spread outward across the land, it also spread upward toward the sky. Because urban property was in great demand, industrialists needed to maximize small holdings. If additional land was too expensive, why not increase space by building upward? The critical invention leading to this development was of course the fast elevator, developed by Elisha Otis in 1861.

Steel provided a plentiful, durable substance that could sustain tremendous weight. Chicago architect Louis Sullivan was the foremost designer of the modern skyscraper. His designing motto was "form follows function." In other words, the purpose of a structure was to be highlighted over its elegance. Beginning with the Wainwright Building of St. Louis in 1892, Sullivan's steel-framed colossus became the standard for the American skyscraper for the next twenty years. Chicago was the perfect site for this new development, because much of the city had been destroyed by a great fire in 1871.

Seeing, Talking, Shopping, and Moving

Few inventions allowed humans to challenge nature more than the light bulb. No longer dependent on the rising and setting of the sun, city dwellers, with their ample supply of electricity, could now enjoy a night life that candles simply could not provide. Developed by Thomas Edison in 1879, urban areas consumed them at a staggering rate.

Alexander Graham Bell added a new dimension to communications with his telephone in 1876. The implications for the business world were staggering, as the volume of trade skyrocketed with faster communications. In addition to the telephone, many urban denizens enjoyed electric fans, electric sewing machines, and electric irons by 1900.

Up, up, and away! New York's Woolworth Building took the city to new heights.

The farm could not compete. Most of these new conveniences were confined to the cities because of the difficulties of sending electric power to isolated areas. Indoor plumbing and improved sewage networks added a new dimension of comfort to city life. Department stores such as Woolworth's, John Wanamker's, and Marshall Field's provided a large variety of new merchandise of better quality and cheaper than ever before.

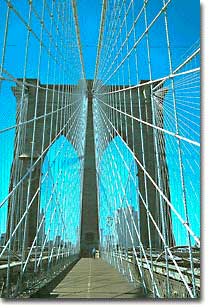

People could reach their destinations faster and faster because of new methods of mass transit. Cable cars were operational in cities such as San Francisco and Chicago by the mid-1880s. Boston completed the nation's first underground subway system in 1897. Middle-class Americans could now afford to live farther from a city's core. Bridges such as the Brooklyn Bridge and improved regional transit lines fueled this trend.

The modern American city was truly born in the Gilded Age. The bright lights, tall buildings, material goods, and fast pace of urban life emerged as America moved into the 20th century. However, the marvelous horizon of urban opportunity was not accessible to all. Beneath the glamour and glitz lay social problems previously unseen in the United States.