49b. Putting People Back to Work

Over 9,000,000 Americans were involved in a multitude of Works Progress Administration projects, from building roads to beautifying government buildings. The above WPA mural depicts the arrival of the first train west of Chicago and can be found in an Oak Park, Illinois, post office.

Out of work Americans needed jobs. To the unemployed, many of whom had no money left in the banks, a decent job that put food on the dinner table was a matter of survival.

Unlike Herbert Hoover, who refused to offer direct assistance to individuals, Franklin Roosevelt knew that the nation's unemployed could last only so long. Like his banking legislation, aid would be immediate. Roosevelt adopted a strategy known as "priming the pump." To start a dry pump, a farmer often has to pour a little into the pump to generate a heavy flow. Likewise, Roosevelt believed the national government could jump start a dry economy by pouring in a little federal money.

The first major help to large numbers of jobless Americans was the Federal Emergency Relief Act. This law gave $3 billion to state and local governments for direct relief payments. Under the direction of Harry Hopkins, FERA assisted millions of Americans in need. While Hopkins and Roosevelt believed this was necessary, they were reticent to continue this type of aid. Direct payments might be "narcotic," stifling the initiative of Americans seeking paying jobs. Although FERA lasted two years, efforts were soon shifted to "work-relief" programs. These agencies would pay individuals to perform jobs, rather than provide handouts.

Of the many programs instituted by the New Deal, the Civilian Conservation Corps was one of the most popular and successful. Here, FDR meets with some of the participants in the CCC.

The first such initiative began in March 1933. Called the Civilian Conservation Corps, this program was aimed at over two million unemployed unmarried men between the ages of 17 and 25. CCC participants left their homes and lived in camps in the countryside. Subject to military-style discipline, the men built reservoirs and bridges, and cut fire lanes through forests. They planted trees, dug ponds, and cleared lands for camping. They earned $30 dollars per month, most of which was sent directly to their families. The CCC was extremely popular. Listless youths were removed from the streets and given paying jobs and provided with room and shelter.

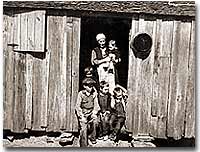

Living conditions during the Depression were often abhorrent. Mrs. Handley and some of her children seek shelter in a shack in Walker County, Alabama.

Earning $15 per week, CWA workers tutored the illiterate, built parks, repaired schools, and constructed athletic fields and swimming pools. Some were even paid to rake leaves. Hopkins put about three thousand writers and artists on the payroll as well. There were plenty of jobs to be done, and while many scoffed at the make-work nature of the tasks assigned, it provided vital relief during trying times.

The largest relief program of all was the Works Progress Administration. When the CWA expired, Roosevelt appointed Hopkins to head the WPA, which employed nearly 9 million Americans before its expiration. Americans of all skill levels were given jobs to match their talents. Most of the resources were spent on public works programs such as roads and bridges, but WPA projects spread to artistic projects too.

Before the advent of Social Security, many unemployed Americans were forced to seek food from shelters and soup kitchens. This Chicago soup kitchen was sponsored by the notorious gangster Al Capone.

The Federal Theater Project hired actors to perform plays across the land. Artists such as Ben Shahn beautified cities by painting larger-than-life murals. Even such noteworthy authors as John Steinbeck and Richard Wright were hired to write regional histories. WPA workers took traveling libraries to rural areas. Some were assigned the task of transcribing documents from colonial history; others were assigned to assist the blind.

Critics called the WPA "We Piddle Around" or "We Poke Along," labeling it the worst waste of taxpayer money in American history. But most every county in America received some service by the newly employed, and although the average monthly salary was barely above subsistence level, millions of Americans earned desperately needed cash, skills, and self-respect.