49d. Social Security

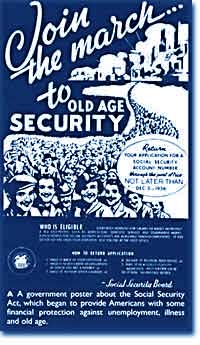

Social Security not only directly aided those who had retired and widows and orphans of insured workers, but it also encouraged states to provide more far-reaching social assistance programs.

Pensions for the retired or the notion of Social Security was not always the domain of the federal government. Individuals were expected to save a little of each paycheck for the day they would at last retire. Those who were aggressive enough to negotiate a pension plan with an employer were few indeed. The majority of working Americans, however, lived check to check, with little or nothing extra to be saved for the future. Many became a drag on the rest of the family upon retirement. The Social Security Act of 1935 aimed to improve this predicament.

Many nations in Europe had already experimented with pension plans. Britain and Germany had found exceptional success. The American plan was a bit different in its design. Social Security was described as a "contract between generations." The current generation of workers would pay into a fund while the retirees would take in a monthly stipend. Upon reaching the age of 65, individuals would start receiving payments based upon the amount contributed over the years.

Businesses that accepted fair trade codes under the National Recovery Administration were allowed to display the blue eagle symbol of the program.

Employees would have one percent of their incomes automatically deducted from their paychecks, a rate that was originally envisioned to reach 3%. Employers would also contribute for their employees. The plan was mandatory except for individuals in exempted professions. Roosevelt knew that this reform would be permanent. He guessed that once workers had paid into a system for decades, they would expect to receive their checks. Woe to the politician who tried to end the system once it was in place.

President Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act into law in 1935. Designed to pay retired workers age 65 or older a continuing income after retirement, this act helped Americans breathe easier about their futures.

A committee of staffers led by Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, the first female ever to hold a Cabinet position, penned the Social Security Act. In addition to providing old- age pensions, the legislation created a safety net for other Americans in distress. Unemployment insurance was part of the plan, to be funded by employers. The federal government also offered to match state funds for the blind and for job training for the physically disabled. Unmarried women with dependent children also received funds under the Social Security Act.

Roosevelt and his advisers knew that the Social Security Act was not perfect. Like other experiments, he hoped the law would set the groundwork for a system that could be refined over time. Social Security differed from European plans in that it made no effort to provide universal health insurance. The pensions that retirees received were extremely modest — below poverty level standards in most cases. Still, Roosevelt knew the plan was revolutionary. For the first time, the federal government accepted permanent responsibility for assisting people in need. It paved the way for future legislation that would redefine the relationship between the American people and their government.