22e. New Roles for White Women

Trends in clothing such as those seen above from the early 1800s, forced a distinction between the wealthy class dressed in European styles, and the lower classes whose simple homespun materials made for more durable, if less attractive, garments.

Who would wear the pants in most American families — men or women? The social change dictated by the Second Great Awakening, to some degree, tailored the answer to that question.

The social forces transforming the new nation had an especially strong impact on white women who, of course, could be found in families of all classes throughout the nation. As we have seen, the early Industrial Revolution began in the United States by taking advantage of young farm girls' labor. Meanwhile, the Second Great Awakening was largely driven forward by middle-class women who were its earliest converts and who filled evangelical churches in numbers far beyond their proportion in the general population. Furthermore, the Benevolent Empire included an institutional place for respectable women who formed important women's auxiliaries to almost all of the new Christian reform organizations.

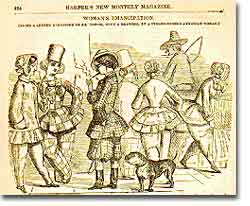

A 19th century cartoon satirizing white women who dressed and acted like men in an attempt to further the cause of women's rights.

Gender implications intertwined with these religious and economic changes. The republican emphasis on equality and independence as fundamental principles of the United States challenged traditional concepts of family life where the male patriarch ruled commandingly over his wife and children. In place of this dominating father-centered standard, a new notion of more cooperative family life began to spread where husband and wife worked as partners in raising a family through love and kindness rather than sheer discipline. A transition of this magnitude occurred over a long period of time and with an uneven impact throughout the country. Middle-class women in the northeast, however, were at the forefront of this new understanding of family life and women's roles. As with the economic expansion of the Industrial Revolution and the reforms of the Benevolent Empire, the northeast was at the leading edge of major social changes in the new nation.

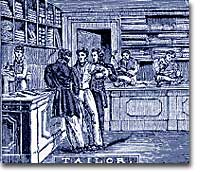

This engraving from 1836 depicts the inside of a tailor shop. When an order was made, bolts of fabric were delivered to seamstresses who would cut the fabric at their homes — for a fee 25-50% less than their male journeyman tailor counterparts.

Assessing the benefits and limitations of these changes for white women has been the source of a great deal of disagreement among historians in recent years, but it is clear that the new developments of the early-19th century helped to establish gender patterns that have remained strong up to the present day. For example, it was only in the 1820s and 1830s that women began to displace men as the overwhelming majority of schoolteachers. This development brought clear advantages to women who increasingly received advanced education to become teachers. Furthermore, teaching brought high moral status and an acknowledged public role in improving American society. On the other hand, the rise of female school teaching also suggests the limited choices available even to middle-class women. They had almost no other options for public employment and were chiefly attractive to employers because they could be paid less than men.

Ultimately, we need to recognize how the rapid changes of this period included both positive and negative qualities. White women came to possess a new social power as moral reformers and were thought to possess more Christian virtue than men, but this idealization simultaneously limited white middle-class women to a restricted domestic sphere. Furthermore, this new standard of womanhood could be achieved neither by working-class women nor by enslaved African Americans.