22f. Early National Arts and Cultural Independence

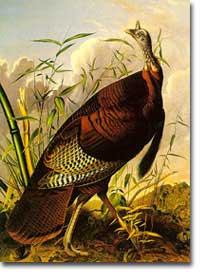

John James Audubon's painting, Wild Turkey, shows a favorite animal of American legend.

Surprisingly, cultural independence proved to be the hardest area for Americans to break free from European models and standards.

American intellectuals and artists recognized the need for American cultural independence. In 1780s, Noah Webster declared that "America must be as independent in literature as she is in politics." His own major contribution to American cultural independence came through an immensely influential spelling book to standardize the American language. By the 1830s over 60 million copies had been sold and its descendent, Webster's dictionary, remains a mainstay of American bookshelves.

Despite the significance of Webster's dictionary, other early national authors were far less successful. The most popular writers of the post-Revolutionary era wrote strongly patriotic accounts, like Mercy Otis Warren's "History of the Revolution" (1805) and Mason Weems' fantastically popular (and distorted) account of George Washington's life that sped through countless editions starting in 1800. Although popular in their day, and responding to a central need to celebrate the greatness of the new country and its leaders, their artistic and scholarly quality suffered from a simplistic patriotic impulse.

Hudson River School artist Frederick E. Church captured the Canadian coast in his painting, The Coast of Grand Manan Island.

On the other hand, the Philadelphia writer Charles Brockden Brown, arguably the most sophisticated novelist of the new republic, reached only a very limited audience with six psychologically-troubling novels published from 1798 to 1801. The first American writer to receive both popular and lasting acclaim was the New Yorker Washington Irving. His most famous stories drew on Dutch-American popular culture in his native state, and gave audiences such classic characters as Rip Van Winkle and the Headless Horseman. Interestingly, however, Irving lived much of his life in Europe and enjoyed a very strong reputation outside the United States.

American landscape painting provided the earliest and most distinctively American contribution to the fine arts. Thomas Cole, an English immigrant who arrived in the United States in 1818, began a painting style that celebrated the American wilderness as a powerful and frightening force that distinguished the United States from the corruption of European civilization. Cole helped to found the Hudson Valley school of landscape painting that frequently painted in that region of upstate New York, a tradition built upon later in the century by men like Frederick Church and Albert Bierstadt who painted further west.

American artist Thomas Cole's Niagara Falls, received rave reviews by the British audience to which it was displayed in 1829.

Ironically, this celebration of American novelty through the wilderness occurred at a time when massive western migration threatened the natural beauty that these artists sought to capture. In fact, artists' need for wealthy patrons and their need to be near these benefactors meant that painters rarely experienced the actual wilderness that they portrayed on canvas.

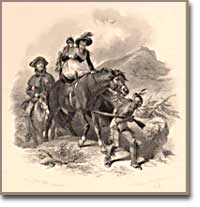

The most celebrated American writer of the new nation was James Fenimore Cooper whose best-known work also emphasized the wilderness and its central role creating America. Natty Bumppo, Cooper's most famous character who appeared in several novels including The Last of the Mohicans (1826), was a heroic frontiersman who recognized the nobility of Native Americans even as he participated in their conquest by settling the west. One painter who addressed this crisis more directly than most was George Catlin. He used Indian portraits to try and raise money and political interest to help Native Americans avoid the destruction of their way of life.

In 1826, James Fenimore Cooper wrote and published one of the classics of American literature, The Last of the Mohicans, a French and Indian War epic that ingrained the nation's romantic and tragic perspective on the plight of Native Americans.

American cultural innovation was both original and thoughtful during the early republic and early national periods. Its most influential contributions generally focused on subjects that distinguished the United States from Europe, like the work of the great naturalist painter and engraver John James Audubon. Nevertheless, landmark American contributions to western creative arts were mostly reserved for a later generation when major figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Thomas Eakins, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and John Singer Sargent would make their marks in the mid- and late-19th century.

At the beginning of the 19th century, All Americans — particularly painters and writers — were struggling with the notion of what it meant to be an America.