26b. Experiments with Utopia

The town of Amana, Iowa operated as a communal society for 89 years. Most of the settlers were immigrants who had left Germany in 1842 and came to Iowa in 1855.

As 19th century America grew larger, richer, and more diverse, it was also trying to achieve a culture that was distinct and not imitative of any in Europe. At the same time, the thirst for individual improvement had local communities creating debating clubs, library societies, and literary associations for the purpose of sharing interesting and provocative ideas. Maybe, people speculated, if any society were completely reorganized, it could be regenerated and, ultimately, perfected. Utopia, originally a Greek word for an imaginary place where everyone and everything is perfect, was sought in America through the creation of model communities within the greater society.

The Shakers believed in celibacy in and outside of wedlock, therefore Shaker children were usually orphans given to the church.

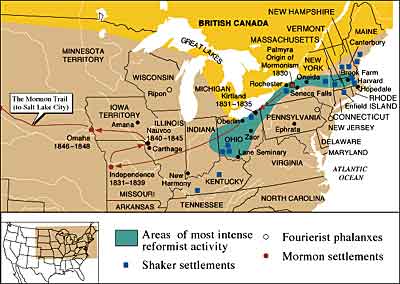

Most of the original utopias were created for religious purposes. One of the earliest was devised by George Rapp, a German zealot, who took 600 followers to western Pennsylvania in 1804. Using shared funds to purchase land, the Rappites created a commune where they isolated themselves from others while waiting for the Revelation. Because of their extreme views on sex and marriage, and their strict, literal interpretation of the Bible, they failed to spread goodwill or gain converts. More hospitable to their neighbors and able to attract about 6,000 members by the 1830s, twenty successful Shaker communities flourished. They followed the principles of simplicity, celibacy, common property, equal labor and reward espoused by their founder Mother Ann Lee.

The founders of Brook Farm tried to create a society of equality for its members.

Gradually, utopian communities came to reflect social perfectibility rather than religious purity. Robert Owen, for example, believed in economic and political equality. Those principles, plus the absence of a particular religious creed, were the 1825 founding principles of his New Harmony, Indiana, cooperative that lasted for only two years before economic failure. Charles Fourier, a French reformer and philosopher, set out the goal of social harmony through voluntary "phalanxes" that would be free of government interference and ultimately arise, unite and become a universal perfect society. John Humphrey Noyes designed Oneida community in upstate New York. Oneidans experimented with group marriage, communal child rearing, group discipline, and attempts to improve the genetic composition of their offspring.

Self-reliance, optimism, individualism and a disregard for external authority and tradition characterized one of the most famous of all the American communal experiments. Brook Farm, near Roxbury, Massachusetts, was founded to promote human culture and brotherly cooperation. It was supposed to bestow the highest benefits of intellectual, physical, and moral education to all its members. Through hard work and simplicity, those who joined the fellowship of George Ripley's farm were supposed to understand and live in social harmony, free of government, free to perfect themselves. However, Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote about his stay here in The Blithedale Romance, left this utopia disillusioned. Finally, it was romantic thinker and strict vegetarian Bronson Alcott, father of author Louisa May Alcott, who devoted himself to tilling the soil at Fruitlands from June 1844 to January 1845 in the hope that love, education, and mutual labor would bring him and his small following peace. He was later ridiculed as "a man bent on saving the world by a return to acorns."

The 1840s marked the height of the utopian trials. The belief that man was "naturally" good and that human institutions were perfectible had raised tremendous expectations about the possibilities of reform and renewal. These experiments ultimately disintegrated but, for a while, tried to be ideal places where a brotherhood of followers shared equally in the goods of their labor and lived in peace. It seemed that within the great American experiment, searching for utopia required only the commitment of people who found it easy to believe that nothing was impossible.