33c. First Blood and Its Aftermath

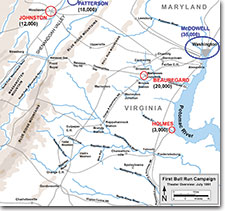

This map shows the situation at Bull Run in July 1861. When viewing the enlargement, note how close the fighting was to the Northern capital of Washington, DC. (Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW [CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

When the war began in April 1861, most Americans expected the conflict to be brief.

When President Lincoln called upon the governors and states of the Union to furnish him with 75,000 soldiers, he asked for an enlistment of only 90 days. When the Confederacy moved its capital to Richmond, Virginia, 100 miles from Washington, everyone expected a decisive battle to take place on the ground between the two cities.

In the spring of 1861, 35,000 Confederate troops led by General Pierre Beauregard moved north to protect Richmond against invasion. Lincoln's army had almost completed its 90-day enlistment requirement and still its field commander, General Irvin McDowell, did not want to fight. Pressured to act, on July 18 (three months after the war had begun) McDowell marched his army of 37,000 into Virginia.

Hundreds of reporters, congressional representatives, and other civilians had traveled from Washington in carriages and on horses to see a real battle. It took the Northern troops two and a half days to march 25 miles. Beauregard was warned of McDowell's troop movement by a Southern belle who concealed the message in her hair. He consolidated his forces along the south bank of Bull Run, a river a few miles north of Manassas Junction, and waited for the Union troops to arrive.

Early on July 21, the First Battle of Bull Run began. During the first two hours of battle, 4,500 Confederates gave ground grudgingly to 10,000 Union soldiers. But as the Confederates were retreating, they found a brigade of fresh troops led by Thomas Jackson waiting just over the crest of the hill.

Naming Battles

The Battle of Bull Run was also known as the Battle of Manassas Junction. Frequently, major battles had two names. The South named battles after the nearby cities. The North named them after the nearby waterways.

Unlike modern-day photojournalists who often find themselves in the thick of battle, photographers hoping to get a shot of the battlefield at Bull Run waited until Southern forces left Manassas in March 1862.

Trying to rally his infantry, General Bernard Bee of South Carolina shouted, "Look, there is Jackson with his Virginians, standing like a stone wall!" The Southern troops held firm, and Jackson's nickname, "Stonewall," was born.

During the afternoon, thousands of additional Confederate troops arrived by horse and by train. The Union troops had been fighting in intense heat — many for 14 hours. By late in the day, they were feeling the effects of their efforts. At about 4 p.m., when Beauregard ordered a massive counterattack, Stonewall Jackson urged his soldiers to "yell like furies." The rebel yell became a hallmark of the Confederate Army. A retreat by the Union became a rout.

Four children watch the federal cavalry at the Battle of Bull Run. Curious onlookers made the journey from nearby Washington, DC to observe the skirmish.

Over 4,800 soldiers were killed, wounded, or listed as missing from both armies in the battle. The next day, Lincoln named Major General George B. McClellan to command the new Army of the Potomac and signed legislation for the enlistment of one million troops to last three years.

The high esprit de corps of the Confederates was elevated by their victory. For the North, which had supremacy in numbers, it increased their caution. Seven long months passed before McClellan agreed to fight. Meanwhile, Lincoln was growing impatient at the timidity of his generals.

In many ways, the Civil War represented a transition from the old style of fighting to the new style. During Bull Run and other early engagements, traditional uniformed lines of troops faced off, each trying to outflank the other. As the war progressed, new weapons and tactics changed warfare forever. There were no civilian spectators during the destructive battles to come.