Errol Lincoln Uys

| Errol Uys Riding the Rails October 13, 2000 |

Ride the Rails with Beyond Books and Errol Lincoln Uys (pronounced "Ace") Friday October 13 from noon-1pm (EDT). Bring questions for the creator of Riding the Rails: Teenagers on the Move During the Great Depression. We've also invited several Depression Era boxcar teens John West and René Champion to join our discussion.

The Great Depression of the 1930s marked a time of unparalleled suffering in the United States. For some, begging, stealing, or going hungry became the norm. Unemployment and poverty rose to unprecedented levels and many took to the rails in search of work or of a better life.

Those who lived through this era have fascinating stories to share. Between 1929 and 1941, many boys, and some girls — often disguised as boys — hit the rails, leaving their families and friends behind.

In Riding the Rails, Uys reconstructs the stories of former boxcar kids using over 3,000 testimonials from former teen hobos. His work, in conjunction with his son's award-winning PBS American Experience Documentary of the same name, accurately displays the courage and strength that it took to make it as a teen on the go during this trying time.

During our session, questions about the danger ("You had to be careful not to stumble and fall under the wheels when you climbed on the cars") and the desperation ("We were always hungry) can be asked. So, work with your class and stock up on questions for these "gaycats" (novice riders) and "dingbats" (seasoned hobos). We'll get to as many as the hour session permits.

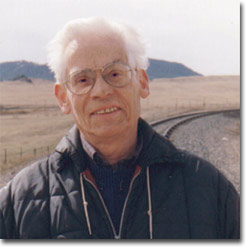

About Errol Uys

Uys's experience has taken him on similar adventures. The author hails from South Africa, where working as a journalist he witnessed the discrimination caused by Apartheid. When Uys tried to speak out against the racism that infected his homeland, his work was censored and subscriptions to Reader's Digest, for whom he was the local editor, were canceled.

But that didn't stop him. He joined forces with the prolific author James A. Michener to help him write The Covenant, which is about South Africa, Apartheid, and the Afrikaner belief system.

Among one of Uys's greatest accomplishments was his book Brazil, a comprehensive work detailing five centuries of Brazilian culture. The book includes the stories of two fictional families, the Cavalcantis and Da Silvas. In order to pen this opus, Uys moved his family to Portugal where he did his research.

Among one of Uys's greatest accomplishments was his book Brazil, a comprehensive work detailing five centuries of Brazilian culture. The book includes the stories of two fictional families, the Cavalcantis and Da Silvas. In order to pen this opus, Uys moved his family to Portugal where he did his research.

It took five years and 15,000 miles of travel by bus for Uys to learn about the people and the land of Brazil firsthand. His descriptions of the country transport the reader to this historical, tropical wonderland.

To learn more about Mr. Uys, visit his website.

Transcript

| US | It's a beautiful autumn day here in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the hometown of Errol Lincoln Uys, author of "Riding the Rails: Teenagers on the Move During the Great Depression." We are conducting our expert session from Rindge and Latin High School in Cambridge, close by Harvard University. Perhaps we can begin with an overview of how you started the project? |

| Uys | The project started seven years ago, when I was doing research on the Great Depression. I picked up a book, "Boy and Girl Tramps of America," by Thomas Minehan, a graduate student at the University of Minnesota. In 1932, as the phenomenon of children riding the rails grew, Minehan dressed as a hobo and rode with the kids. When we study the Great Depression much is statistical — I was riveted by Minehan's book that connected me to the lives of young people of the time. My son had just finished NYU film school. I told him to read "Boy and Girl Tramps" and suggested the subject would make a great documentary. He agreed. His first step was to contact people who did this. He put a small notice in "Modern Maturity," the AARP magazine, the association of retired people, expecting one or two hundred letters. He received three thousand letters from every state in the country, which was an early indication of what the subject meant to people. |

| US | How many teens took to the rails during the Great Depression? |

| Uys | A quarter million. |

| US | What were the reasons, I know there must be many? |

| Uys | Many, many reasons. The most important reason, of course, was desperation. Their whole home structure collapsed. They had no opportunities. In many cases, their schools were closed. We'll get into that later on. The majority hit the rails because of the effect of the Depression on their families. |

| US | Were these boys and girls? Were there girl hoboes? |

| Uys | Thomas Minehan, because he was out there, did the one estimate we have of the number of girls. He figured that one in ten who rode were girls. For her own safety, a girl was going to dress as a boy, cut her hair short, and travel in disguise. |

| US | We are going to be taking questions from our schools now. I have the first question, please. Okay. Who has a question from the studio audience? Yes, sir. |

| Uys | The youngest hobo? Some of the letters revealed that children of nine years old were out by themselves. You found families, particularly women and their children, on the road. There is a tragic story of a young woman with three kids — four, six, and nine years old — She traveled from the Midwest to Sacramento every summer for four years with her kids and a little dog. They rode the freights to work the harvests. |

| US | How frequently did people die from accidents and such? |

| Uys | In 1932, a government study estimated that 5,000 people were killed or injured: Of those 5,000, 1,500 were under 21 years of age. A minister who wrote from New York made an interesting comment: At the time, there were no Social Security cards. These kids rode the rails without any identification: In many cases, a boy or a girl was found dead beside the railroad with no ID. "They were the MIAs of the Great Depression," the minister said. We have several stories of people who rode the rails and were never heard of or seen again. |

| US | Errol, did the hoboes have their own jargon or special language? |

| Uys | Yes. They had signs, for example. This hobo tradition went back long before the Great Depression to the previous century. Before mechanization, migrant workers, many of who were hoboes, harvested crops. Train companies would leave boxcars open so that workers could get to the fields; the harvested crops would be transported by the railroads. So... |

| US | We're looking for a special language. |

| Uys | The older hoboes would scratch signs on fence posts and trees near people's houses. For example, a sign might indicate that it was a good house for a handout, where food was given. Or perhaps the sign warned about a dog or a house where a policeman lived. Over the years, hoboes developed a definitive sign language. |

| US | I have heard of hobo jungles. Could you elaborate on what those were? |

| Uys | Outside the major railroad yards there was a hobo jungle, basically a camp where hoboes got together to cook their food. In many camps, there were older hoboes — "jungle buzzards," they were called — who would build a shack and live there permanently. When the kids came along, the old buzzard would say, "you get me potatoes," "you fetch meat," "you go and ask for coffee." The kids were sent into town: They were young and innocent looking, so it was easier for them to get stuff. When they brought it back, the old hobo would cook a meal: a mulligan stew, the traditional hobo meal. One boxcar boy recalled that if the old 'bo liked the look of you, when he dished out the mulligan, he went deep and fished out bones with meat. If he didn't like the look of you, he gave you flavored water. |

| US | You tell a very touching but horrifying story of African-American boys in your book. Tell us what happened to them... |

| Uys | In the south, if you were African-American it was going to be doubly hard for you if you rode the rails. The case of the Scottsboro boys was notorious and horrific: very briefly, two white women accused eight African-American kids riding the rails of assaulting them. The accusations were false. The boys went through several trials and were sentenced to death. Some spent the rest of their lives seeking to exonerate themselves. |

| US | Were there racial tensions among hoboes? |

| Uys | Most of the letters I have work the other way. A lot of the young white hoboes hitting the rails never had contact with black kids. They were thrown together under these tough circumstances. Many anecdotes relate to the shared experience as a leveling thing. You were suffering together. But there are instances, too, of African-American kids beaten up in racist attacks. |

| US | There was a wonderful story by a hobo named John West. Would you relate his journey from Texas to New Orleans? |

| Uys | John West ran away from home. He headed to New Orleans and ended up in Canal Street. He's walking down the street, terribly hungry, away from the bright lights of Canal Street to where it gets darker and darker. He goes into this small restaurant and sits down to eat. It's near the end of the meal that he realizes he walked into a restaurant filled with African-American people. He gets up and goes to pay the 15 cents for the meal. "I'm glad you enjoyed the food. Keep your 15 cents," the owner said. John never forgot that incident. He wondered for years what would it be like for a black kid if he walked into a white cafe. It affected his entire viewpoint of life. |

| US | We have questions from schools now. |

| Uys | Okay. |

| US | This question's from Pennsylvania. After the Depression ended... |

| Uys | You hit the rails for three or four or five months during the summer. You went back and spent a period at home. In certain cases, children would find the situation at home had not changed or had become worse. They would leave again, in many cases with their parent's permission. There were few instances among the three thousand letters where a boy or girl's leaving caused a permanent rift in the family.Clarence Lee was 16, a sharecropper's son, when he had to leave home. His father turned to him one night and said he had no money. "I cannot feed you. Go fend for yourself." There were many families equally desperate. Rarely was there a total separation between a kid and his family. |

| US | From Travis in California. Go ahead. Was there stealing between hoboes? How was order kept between the hoboes? |

| Uys | Few instances of stealing are revealed in the letters. There was a code of honor among hoboes. For example, in the jungles, there was an unspoken rule that you left the jungle in good condition for the next guy coming along. You cleaned up before you "caught out." If you had coffee, you left the coffee grounds there. One man wrote about coming to a jungle: "If you were lucky, you might be able to get a pot of coffee out of the grains that were left."There is little evidence of theft. One young man does mention though how he landed in a boxcar with two older hoboes. When he was sleeping, they went through his pack and took his belongings, what little he had. |

| US | Travis, thank you. Our next question comes from. New York: Lisa wants to know are there hoboes today? Are there similarities and how do they live? |

| Uys | In August, I went to the National Hobo Convention (Britt, Iowa.) Yes there are hoboes, and many exaggerated stories about them. Such as happened when a man who rode the rails was convicted of murder in Texas. Today's hoboes are a small group: I estimate two to three hundred genuine old style hoboes. — With the term "hobo," you distinguish between "hobo," "tramp" and "bum." A hobo works for a living. — I have met some of today's hoboes: There's a man from Texas, for example, who has hoboed since he was 22 years of age; he's 47 now. He never begs for a living. He always works. For example, he will come to a small town where he knows someone; he will wash dishes for a couple of days. — In the 1930s, the expression for washing dishes was "pearl diving." There are homeless kids who ride today — Hopping freight trains is extremely dangerous. |

| US | Our next question comes from Tinky in New Jersey. He asks: how did hoboes bathe, clean their clothes, and even go to the bathroom? |

| Uys | Interesting question. The kids went out of the way to keep themselves clean. In a word, it had to do with keeping their dignity. Besides, you had to keep your appearance reasonably good and clean, if you were knocking on people's doors to ask for food. If you looked relatively clean cut, your chances of a handout would be much easier. They would wash up in the hobo jungles. For the older kid who needed a shave, there would be a razor hanging from a tree in the hobo jungle. The hobo carried his own blade for the razor. They kept themselves clean. |

| US | As a follow-up, did they keep themselves up on what was going up culturally, music, sports and read papers? |

| Uys | Relatively few did, from the letters. With sports, some letter writers recall listening to fights or ball games, standing around a radio in some small town. Interestingly one of the riders said pointedly that there were few in-depth discussions. The number one topic was — "Where are the jobs?" There are poignant tales of kids on one train going west; other kids on a train going east. Sitting in groups on the top of the boxcars. The kids heading west say, "There are no jobs." The kids going east say "No jobs." They still go their ways, in desperation to find something. |

| US | Wow. |

| Uys | Many of these kids' lives were changed by the experience. |

| US | I bet. |

| Uys | You have, for example, the story of John Fawcett, the son of a wealthy ophthalmologist in Wheeling, West Virginia. When he hit the rails, he was running away from home because he didn't like his school. He lands in the Ozarks, in Marshal, Arkansas, a small town battling to survive through seven years of Depression. John was listening to people on the edge of poverty telling him things he never heard in his life. So later, when he went back to school he had great difficulty coping with the lack of understanding or acceptance of what was going on in the country. The end result was that for the rest of his life John became a fighter in civil rights, gay rights, women rights. John says that without any doubt, the period he spent on the rail in 1936 changed his life. |

| US | Now a question from the studio audience. Yes, sir. |

| question | [indecipherable] |

| Uys | I can't say. It's likely that something like that happened. You would find kids that were often separated. You had two buddies that traveled, say from Boston to the Midwest. You got to one of the huge railway yards late at night and lost each other. It could be months before you saw each other again. |

| US | Uh-huh? |

| Uys | Sometimes, the boxcar kids pulled tricks, too. A kid would go to a house and knock on the door and ask for a handout. He would say, "My dad is waiting back there and he's hungry." That way the kid got two meals. You learned a lot of tricks on the road just to survive. |

| US | Todd from Arizona writes in. Did a lot of the hoboes get jobs with the military as the Depression waned? |

| Uys | There were two major ways off the road. The CCC — Civilian Conservation Corps — was established just after Franklin Roosevelt was elected. By the first summer, a quarter million kids were in camps around the country; between 1933 and 1941, 2.5 million young men served in the CCC. They were paid $30 a month, of which $25 was sent home to their families. In many cases this was all the income the families had. ... What really ended the Great Depression was World War II. Many of the kids riding the rails went into the military — the "Depression doughboys." |

| US | Jo-Jo from El Paso, Texas asks how willing were people to give hoboes food as they wandered through the towns? |

| Uys | One has to realize there were small towns like Demming, New Mexico, where the population was about 3,000. — The town would be hit by 125 hoboes a day of all ages. This put a tremendous strain on resources; there was a policy of "passing on" hoboes to the next town. But generally towards the road kids, there was compassion. They were given food. They were helped. And there was an understanding of what this meant to the dignity of the kids. Imagine, all of you sharing in this program — imagine what it would be like to go out today and knock on someone's door and ask for food. A glass of water or milk? It was really tough. There are countless stories of homeowners, who would say to a kid, "Go and chop that wood." "Go and pull those weeds." Just so the kid wouldn't be begging. We had letters from people who didn't ride the rails: they remember as kids, how their parents treated hoboes coming to their house with compassion. |

| US | Sure. |

| Uys | That stuck with them for the rest of their lives. |

| US | Brett from North Dakota asks what kind of crimes were hoboes charged with? Referring to loitering crimes. |

| Uys | Caught trespassing, you were pulled off the trains and arrested. In particular parts of the country, particularly the Southeast, you were taken to the county courthouse and charged with riding the rails illegally. They would sentence you to a month's work on a farm, where crops needed picking or working on the roads. In many instances, the system of justice was arbitrary. In certain areas, where a county had work that needed to be done, it was convenient to pull hoboes off the trains. |

| US | Todd checking with us again. Were there particular regions favored by the hoboes? Did they move south in the winter and north in the summer — like birds did they migrate? |

| Uys | Absolutely. There were obviously favored regions in California and the Midwest. They followed the traditional migration of workers harvesting crops from California to the north and the apple fields in Washington. Here in the Northeast there was little opportunity for hoboes. There were places they chose, and places they avoided, like the Southeast, where they knew they would get in trouble. |

| US | Annie, who is a biologist from Louisiana, has a question. Was Woody Guthrie a hobo? |

| Uys | Yes. |

| US | We have another question from the studio audience. |

| question | The question is, were there similarities between hoboes and indentured servants? |

| Uys | I wouldn't think so. Remember the hobo was free to come and go. Hoboing wasn't contractual. A hobo would arrive at a farm, for example, for the harvest season. A "harvest tramp" would pick the crop and move on. There were no contracts. The romantic image of the hobo's free and easy-going life predates the Depression, of course. — I think the hobo's life is very different. |

| US | On the phone now we have John West who was a hobo. First of all, I would like to open the floor to the studio audience. Any questions for John West? Yes, sir. |

| question | Mr. West, thank you for participating. |

| US | He says, hello, as well. |

| question | The question is: did you travel by your self or in a group? |

| West | Always by your self. |

| question | How come that was? |

| West | Now, you went from Texas to New Orleans. |

| question | Can you tell us about that, Mr. West? |

| US | I actually have to translate while — this is a very crude form of technology. Sorry. I have to inform the studio audience of what you're saying. Okay. Let me catch them up with you. Basically, he told of going out from his home in Texas and on his way to New Orleans. Okay. Okay. Let me translate that. He traveled from El Paso to Mississippi where he had family. Okay. What, what caused you to run away from home? Okay. He actually ran away from home. He had two nephews who stole his football and left it in the weeds. That's a good story. Okay. We're going to take some more questions. I'll put you on standby now. Thank you. Tiffany asks what kind of jobs did hoboes have and were some easier than others? |

| Uys | Not the easiest jobs. Few of the kids got permanent jobs. Most of the work was in the harvest. Those are the main jobs. Maybe they got a small job for two or three days, made a little money and then moved on. Remember, there were no jobs for adults. There were very, very few jobs for kids. |

| US | Phil from Philadelphia asks, Was there love found on the rails? Were there marriages made? What did people do in that department? |

| Uys | There's one particularly great story about a couple who rode the rails in Texas. He would ride to visit his girlfriend. After their marriage, they rode the rails with their six-month-old baby to visit their in-laws. We have a couple of stories of kids who met like that. There are also stories of girls who were forced into prostitution. |

| US | Were they paid? |

| Uys | Yes. The anecdotes come out of Thomas Minehan's book. He tells several harrowing stories. |

| US | Tiffany asks, from California, is it difficult to jump off a moving train? |

| Uys | Difficult and dangerous. |

| US | Instances of injury I assume? |

| Uys | It's in the book. Fatal injuries. |

| US | We have more questions for Mr. West. Mr. West, are you still there? Okay. Lisa from Pennsylvania asks: would you recommend the hobo life to kids today? Okay. Thank you. He says, no. There are easier ways to make a living. Don't try this when you get off of school today. I have one for you, Errol. Was there an average time length people spent on the rails? |

| Uys | Yes, I would say that on average it was three to six months. |

| US | Three to six months. |

| Uys | But some went as long as ten years. |

| US | Were the teenagers political at all? |

| Uys | Some of them were. James San Jule's father was a millionaire in Tulsa, Oklahoma and lost everything in the Crash. James rode the rails and ended up in San Francisco during the 1936 dockworkers' strike. He became involved with this fight. One man from New York wrote that his time on the road made him a life-long liberal. We have letters from people of the Depression generation, who talk of never letting their pantry go empty. They're terrified of bring hungry again. |

| US | Alberto from Chicago asks if hoboes had the sticks with handkerchiefs attached? |

| Uys | This is the Charlie Chaplin, happy tramp image. There was little happiness in what was a really tough life. |

| US | Mr. West, Lisa has a question for you. Do you consider the word "hobo" pejorative? ... (On phone) Thank you for that. For the studio audience, basically no. It was not a negative term. The term "homeless" wasn't coined yet. Mr. West is not so happy with the term "bum," however. It's asked, were there particular hobo camps known for their good mulligan stews or hospitalities? |

| Uys | Yes. Offhand, I can't recall which ones, but there were. |

| US | Alberto has a question for you. Why did you think it was important to tell the story of hoboes? |

| Uys | Involved in the 3000 letters, you began to see an enormous part of history that was not told: Images of the Great Depression through the eyes of teenagers. From the three thousand letters, we concentrated on 500: the book was finally comprised of the stories of about 250 boxcar boys and girls. As we go further away from the Great Depression, it's difficult for young people today to connect to the events. As I said in the beginning, there are statistics and facts, but to actually connect to the people. — That's one of the marvelous things about this subject. |

| US | Mr. West, we have another question for you. Were you ever afraid on the rails? What scared you? ... For those in the audience: Yes. He was scared often. Also, for a hobo, it's physically demanding. I have one for you. Did you do a lot of background reading for knowledge of the era? |

| Uys | I researched the various government hearings held at the time, such as those on the American Youth Act, the National Recovery Act. Plus other essential sources for the introduction...But the letters themselves give a full picture of the period. |

| US | Dan, from the studio audience. |

| Dan | My question would be: to my understanding hoboes do exist today. Especially between Florida and Maine here on the east coast with the commute between orange and apple picking seasons. As far as I know, the methods of travel are the cheapest possible. I know that some people have vehicles. It may not be the railway, but it's the same style of life. Camping and making ... |

| Uys | Absolutely. We were talking specifically about riding the rails. You are right. The Mexican migrant workers are probably the closest to the hobo of that period in their lifestyle. |

| US | We actually have a question from Moscow. Ed asks, "Did hoboes come from all walks of life or were they a specific people, mainly hoboes?" |

| Uys | All walks of life. There was no particular hobo group in the Great Depression. There were four million people riding the rails. I concentrated on the 250,000 teenagers. |

| US | Sure. |

| Uys | Is that Moscow? |

| US | The former Soviet Union! |

| Uys | One of the things I write about in the book are the homeless kids left after the Revolution. There were up to 800,000 roaming Russia. The New York Times wrote about these "bezprizorni." There were kids of six and seven years old carrying guns and robbing people in Russia at that time. Their images colored the thinking about the U.S. teenage hoboes. The fear was the 250,000 teenagers would turn into these huge gangs of kids. |

| US | Alberto from Texas asks, "There were boxcars and gondolas. What was the preferred way of moving?" |

| Uys | A boxcar. If it was open, and you could ride inside. The most intrepid kids would ride what was known as the "blinds" on the first car behind the engine. You got in twice as much trouble if you were caught there. Kids also rode the tenders attached to the engine. Sometimes the engineer would drag kids off the tender. "If you want to ride, you have to work." They made them shovel coal for a couple of hundred miles. |

| US | Annie from Louisiana has a question: "Did people ever get arrested on purpose to go to jail ... did the hoboes? |

| Uys | I don't have any record of that. But we have letters of people who went to a police station and asked if they could sleep overnight. In places they would allow to you do that, even give you breakfast. Maybe you had to sweep out the jail. One boy was put into an older section of a police station. They forgot him and left him there for 36 hours. |

| US | You have kindly brought some photographs today. Tell us what's going on in the photos? |

| Uys | These are classic photographs from the Library of Congress and National Archives. They were taken under the auspices of the FSA (Farm Security Administration) and the WPA (Works Projects Administration.) They sent some of the finest photographers in America to chronicle the Great Depression. These pictures come from a collection of 77,000 photographs of the period, one of the most valuable records of the era. This is an interesting picture: It was on the poster for the documentary, "Riding the Rail." Someone walked past it in Washington State and said, "That's my father." |

Excerpts from René Champion

Writing about the years 1937-1941

"I looked at the hill behind our house and at the blue sky above. I wanted to reach the other side of the hill and see what was there."

The impulse that drove René Champion to leave Johnstown, Pennsylvania in 1937 at age 16 kept him on the road for the next four years. René was born to an unwed mother in Paris in 1921. When he was eight months old, his mother placed him in a children's home and emigrated to America. He did not see her again until she sent for him in September 1929. Arriving in the United States on the eve of the Great Depression, René's boyhood years were marked by want and poverty.

I can understand why my mother left me in France. In those days it was scandalous for a woman to be an unmarried mother. But at eight-and-a-half years, I never knew what it was like to grow up with a mother and my mother didn't know how to raise a child.

I was raised in what would today be called a dysfunctional family. My mother was a high-strung person, strong and demanding. She never realized her ambition to be a fashion designer, which left her frustrated. One result was constant warfare between her and me. 'I'd never amount to anything,' she would say. I was just a 'bum' and a 'no-good.'

My mother let out her anger toward me by hitting me with whatever she happened to have in her hand like a pot or a pan. More than once she came at me with a knife but restrained herself. Rare were the times that I went to school without a couple of lumps on my head or black and blue marks.

"There was no question that the Depression was a big factor. Had we been living in happier times economically, I think things would have been different. My stepfather was 24 years older than my mother. He lost his business in the 1929 Crash and became a traveling salesman. He later worked on a WPA project. There was very little money coming in, which added to my mother's unhappiness. We went on relief until my father found a $10-a-week job in a department store, hardly enough for us to live on but it was better than nothing.

It was a humiliation for my mother to accept charity. I remember my mother and I going to steal coal in the Johnstown rail yards. We nailed a wooden keg onto a sled and pulled this to the tipple, where we filled the keg with lumps of coal. I climbed on top of loaded cars and throw coal down to my mother. I was always afraid my school mates would see me at the tipple.

I had to wear hand-me-down clothes given to us by charitable organizations. Kids were not nearly as fashion-conscious as they are today but they could tell a shirt or a pair of pants that was 20 years out of style. I remember being forced to wear girl's shoes because they were the only pair in a package of clothing given to us. The kids at school made fun of me. I told them that the shoes were the latest fashion but they knew I was lying. I got into a couple of fistfights trying to defend myself.

I used to run away for two or three days. The police would pick me up and bring me back. I'd stay home for two or three weeks, then run away again. Eventually I was taken to juvenile court, where a judge decided that I was incorrigible and sent me to the Cambria County Children's Home for two months.

My first day at reform school I was sitting at a long bench table at breakfast. I turned to my neighbor to ask a question. Bingo! Next thing I knew I was lying on the floor with a terrible pain in my side. A guard stood above me holding a long stick which he used to knock me off the bench. "We don't talk at meals," he said. I had to watch every move I made in the next two months.

One thing I give my mother credit for: She instilled in me a respect for education that made me stick things out until I got my high school diploma. After graduation, I decided to run away for good. It wasn't only my unhappiness at home but a yen for wandering. The horizon has always had an irresistible lure for me. Running away so many times, I learned a lot of street smarts that would be very useful to me as a hobo.

I remember the day I left home. It was sunny and bright. My heart was light and I felt a certain freedom. I was finally getting away.

I was drawn to the West by the cowboy movies I'd seen filled with romantic images of the great plains, the mesas and monuments and the immense vistas of the horizon miles and miles away. Coming from the eastern part of the United States and suddenly emerging on those vast open spaces, I realized this was a world I was in tune with. It filled me with a special joy and made me feel at home.

The first time I tried to hop a freight train outside Johnstown I was lucky not to be injured. The train was going too fast and I didn't grab on tightly enough. My body hit the side of the car and I was thrown head-first into the cinders. My face and hands were cut up and my clothes torn. I decided to hitch hike. Leaving the railroad tracks, I had to wade through a stream polluted by effluent from a steel mill. When I finally stuck my thumb out on the road, I was such a sight that nobody stopped for me.

I walked 50 or 60 miles before I got a ride with a trucker outside Harrisburg. He was heading for Philadelphia and that's where I went. If he'd been going to New York or Toronto, it would have made no difference. I was ready to go in any direction.

I hitchhiked Route 22, the William Penn Highway, to Chicago and then took Route 66 through Illinois, Missouri and Oklahoma down to the Texas Panhandle. When I got into Arizona and New Mexico there were so few cars that I had no choice but to ride freight trains to travel further west.

Experienced hobos taught me how to hop a boxcar safely. Most of the hobos were older: in their mid-20s and 30s. You'd see 12 or 15 hoboes sunning themselves on top of a boxcar, sometimes as many as 200 or 300 together on a train looking very much like lines of blackbirds on telephone wires. Two trains would frequently cross each other on adjoining tracks, with some hoboes going west, some going east, all looking for jobs.

I worked whenever I could but seldom stayed anywhere very long. I did a lot of migratory farm work. I picked string beans and tomatoes in New Jersey, strawberries in Maryland, oranges and grapefruit in Florida. I cut wheat in Kansas. I pulled peanuts in Texas and broom corn in New Mexico. For a time, I also worked on a cattle ranch in New Mexico, a real live cowboy like my movie heroes.

One of the most moving memories of my days on the road is of a young couple with a baby who rode with us on a Southern Pacific freight. There were probably a hundred hoboes on the train when we pulled into Yuma early in the morning. The train was scheduled to stop for a few hours.

Everyone except the family with the baby got off. The hoboes went up town to beg for food. They came back with milk, cereal, fruit and bread which they gave to the young parents.

It was like 100 Magi instead of three bringing gifts to the infant.

One Sunday I climbed off a boxcar in San Jon, a small town in New Mexico. At the local general store, where I offered to work for some food, I learned that Pearl Rasnick, an old widow who lived 10 miles down the road, was looking for a farmhand. I walked out to her ranch and got the job. She couldn't afford to pay me but would give me food and a roof over my head.

Pearl Rasnick was a devoutly religious woman whose one pleasure besides reading the Bible was to attend revival meetings. San Jon was literally a wide place in the road, Route 66 its main street, with seven churches in town.

Pearl had an old Model T in which I drove her to a revival meeting at the Methodist Church. This was the biggest church in San Jon and had the largest congregation. The revivals were conducted by itinerant evangelists, "Elmer Gantry" types, who could be very persuasive.

I was listening to the evangelist's harangue, when all of a sudden I felt a surge of electricity go through my body. I felt a force lift me out of my seat and drive me up to the altar. I had tears running down my eyes. The evangelist saw how moved I was and didn't stop me from addressing his audience. I appealed to the congregation to rededicate themselves to Christ. Usually half a dozen people would go up to the altar but that night practically everybody came forward.

The congregation knew that I was a young hobo who had hopped off a freight train a few weeks before. When the evangelist left, they asked the regular minister, Reverend Tossel, if he would let me preach to them. He was responsible for three churches and needed help so he agreed.

At 17, I became a lay preacher and spoke in one of the churches each Sunday. I felt at peace with myself, even believing that this was what I was seeking in my life as a vagabond.

But I was also a person who needs a rational explanation for things. I started asking myself how I could preach the existence of an all-knowing, all-powerful, all-beneficent God? What proof did I have of His existence? I didn't realize it but that question was the first crack in my faith.

I told Reverend Tossel that I'd begun to feel insincere. "It's the devil testing you," he said. "It happens to all of us. Fight it. Don't let it get the best of you."

I was losing the battle. More and more I asked myself questions that I couldn't answer, until I could no longer live with my doubts. I woke up one night in the middle of the night, packed my few belongings and walked out of San Jon ending my brief career as a preacher.

I knew hunger and cold, nights in jail for vagrancy and beatings by railroad bulls but most people realized I wasn't a hardened hobo. I looked young and was polite and well spoken. People took pity on me, more than they would with older men. Women on the farms where I worked felt maternal toward me.

My experiences on the road gave me a great appreciation for this country — both its physical beauty and for many of the people I met: Honest hard-working people with a good sense of values, who were kind and generous to me on the road.

I remember getting off a train outside Tucumcari with another hobo. The Tucumcari railroad bull had a reputation of being a killer. Neither of us knew whether this was true or false but we weren't taking any chances. We left the freight two miles out of town and walked the rest of the way. The first building we saw on the outskirts of Tucumcari was a diner.

The owner stood in the doorway wearing a white apron that came down below his knees. He called us over.

"I've been watching you walk up that road," he said. "You have a hungry walk about you."

My boxcar partner and I had come from Los Angeles and hadn't eaten for a long time. As we rode together we'd been telling each other what we would buy if we had a dollar. I wanted a deep-dish apple pie or a half a dozen hamburgers.

The owner of the diner had set out food for us. We offered to work for our meal, but he said no. "I know what it's like to be hungry. I'm glad to help you," he said. It was heartwarming to know that a total stranger cared for you.

I would go back to Johnstown periodically and spend a month or so at home. Johnstown lay in a hollow surrounded by hills blackened by soot and slag from the coal mines and mills. It wasn't long before I'd begin to think of the great open spaces and the sunlit Western ranges that I'd traveled. The wanderlust seized me again.

Hoboing is a lonely business. You're far from the town that you grew up in. You're removed from the people and friends that you knew. You're among strangers, each of them going his own way.

The wide open spaces of the West enhance the feeling of loneliness. When I was hitchhiking in Texas and New Mexico, I would sometimes be picked up on the highway and given a ride that ended five or six miles down a dirt road. "Here's where I turn off to my place," I'd be told. I'd be stranded there all night with not a single winking human light in sight, overwhelmed by that immense star-studded sky. The night silence is so dense that it attached itself to you like a second skin. It was tough, very tough. More than once I cried. I felt so sad, so utterly alone.

I could characterize my social life while I was riding the rails in one word: non-existent. You're constantly on the move and don't establish relationships, certainly not with women. Firstly, there weren't many women riding freight trains. And secondly, women in the villages and towns where we passed didn't want to have anything to do with us. We were hoboes willing to work but we were viewed as bums. We dressed like bums, we looked like bums, we smelled like bums.

I have often been asked, "What kept you going? What kept you alive?" I knew hunger, cold, nights in jail after being picked up for vagrancy by railroad bulls. I was lonely all the time, sometimes to the point of being unbearable.

What kept me going was the freedom of it — And my curiosity to see what lay on the other side of the mountain or beyond the next horizon.

In 1940, while hitchhiking in New Mexico, 19-year-old René Champion was picked up by a dean of the University of New Mexico, who convinced him to attend the college. He tutored French to pay for his tuition and worked in the dining hall for his meals. The year he spent at the University of New Mexico sparked an interest in anthropology, which would later be his chosen career.

In August 1941, Champion's wandering days ended when he heard General Charles de Gaulle's call to arms and joined the Free French Forces. He signed up in New York and sailed for Europe, where he was assigned to the famed 2nd French Armored Division, serving first as gunner and later as tank commander. On August 25, 1944, in the liberation of Paris, his tank (dubbed "Mort-Homme," for the name of a WW1 battle) was set ablaze as he stormed the German headquarters. Oblivious of his wounds, Champion fought to extinguish the fire and drive the tank to safety. He had a second tank blown up under him before coming back to the U.S. as a decorated war hero. In 1994, the French government bestowed the 'Légion d'Honneur' on Champion.

On his return in 1946, Champion went back to school and earned his Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia University. After a ten-year academic career, he joined a Rand Corporation think-tank, doing research for the US Air Force. He later worked as a strategic planner for several corporations, including Johns-Manville in Denver. Retiring in 1990, he went back to teaching, as a part-time professor of Anthropology at two Denver universities.

The memories of a lonely runaway in 1937 have never faded. On a day more than half a century later, Champion walks down a country road outside Denver, the train tracks just a stone's throw away. The aging boxcar philosopher retraces his steps on a rite of passage from youth to maturity.

If I had to do it over and choose between going on the road or going to college after high school, there's no question I would do exactly as I did. My experience on the road gave me self-confidence. I overcame a profound shyness and saw that I could shift for myself. I could survive and be respected by people. Without that experience I don't know what kind of person I would've become because I was so beaten down psychologically and emotionally as a child.

As Champion watches a long freight come into view and roll across the Colorado landscape, his memories move him to tears.

The sight of that train, the smell and sound of it makes me cry. It reminds me of the freedom of the road. It is such a sharp contrast to the life I lead now, which is completely organized every moment and hour of the day. On the road, I would have been on that train. I would have gone wherever it lead me, its whistle a siren song that reaches deep down and pulls you along.

Watching that train pass, I sense that I am saying goodbye to an innermost longing for that old freedom I knew. It makes no sense. It's no way to live, certainly not now.

Excerpts from John West

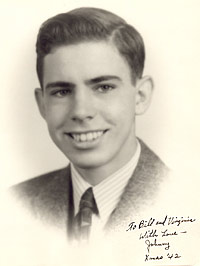

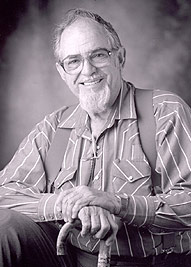

John West in his youth |  John West today |

When John West, a 17-year-old runaway from Texas, reached New Orleans he had 15 cents in his pocket. He walked along Canal Street wondering how to fill his empty stomach; the bright lights and people enjoying life didn't seem to hold out much hope for a hungry boy. Then he came to a poorly lit section of Canal that had few pedestrians. Here is an excerpt:

"I went into a small café and sat down at the counter. A waiter came over and I told him my story. 'Could he serve me something for 15 cents?' I asked."He told me to sit down at a table. He brought a plate piled high with food, including spicy black-eyed peas. It was the best meal I ever hooked a lip over.

"When I sat back to enjoy the feeling of being well-fed, I saw that I was the only white in the café. Cook, waiter and customers were all black, something I hadn't noticed in my hunger to eat.

"When I laid my 15 cents on the counter, I told the waiter the food had been very good.

"'That's what we always serve,' he said. He pushed my 15 cents back across the counter.

"I had tears in my eyes as I left. I couldn't help wondering what would have happened if a little black boy had showed up in a white café."

| One textbook | Up to $300 |

| US textbooks, annually | $10 billion |

| ushistory.org | free |

Meet the Historians

These renowned historians and experts chatted with students online. Read the transcripts.