George Washington:

The Commander In Chief

My inclinations are strongly bent to arms.

~ George Washington, letter to Col. William Fitzhugh, November 15th 1754.

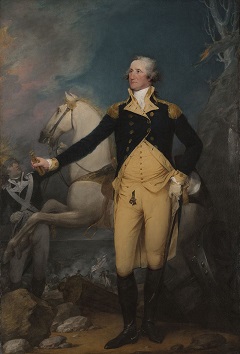

George Washington is best remembered as the first President of the United States, but there might not ever have been a United States, had Washington not so ably performed in the role for which he seemed to have been born: Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army.

His experiences in the French and Indian War were invaluable in teaching him the subtleties of warfare on the American continent. Serving the British crown in their war against the French in the 1750s would prepare him for the conflict that emerged two decades later: Fighting for Independence from the crown he once served, in alliance with the French he once fought against.

Asked to name the greatest man in the Congress, Patrick Henry replied:

"If you speak of eloquence, Mr. Rutledge of South Carolina is by far the greatest orator; but if you speak of solid information and sound judgement, Colonel Washington is unquestionably the greatest man on the floor."

Washington was a member of the Virgina House of Burgesses from 1758 until 1775. Speaking before a meeting of that body soon after the Boston Tea Party, after the British closed the port of Boston Washington asserted: "I will raise one thousand men, subsist them at my own expense and march myself at their head to the relief of Boston."

On April 18, 1775. Major Pitcairn of the British Army fired upon the American militia assembled on Lexington Common. It was the "shot heard 'round the world." The American Revolution was underway. Milita groups from throughout the colonies made their way to Boston.

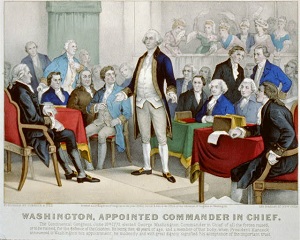

One of the first steps of the new Continental Congress was to organize the army gathered about Boston, calling it the Continental Army. John Adams, of Massachusetts, nominated Washington, then a colonel in the Virginia militia, to serve as commander-in-chief of the army, recording in his diary:

I had no hesitation to declare that I had but one gentleman in my mind for that important command and that was a gentleman from Virginia, who was among us and very well known to all of us; a gentleman, whose skill and experience as an officer, whose independent fortune, great talents and excellent universal character would command the approbation of all America, and unite the cordial exertions of all the colonies better than any other person in the Union.

Adams was persuasive, and Congress concurred with his recommendation. Washington accepted the appointment, but it was the standard practice to make a great show of humility when thus honored. Washington did so in his acceptance speech :

I beg they will accept my cordial thanks for this distinguished testimony of their approbation. But lest some unlucky event should happen, unfavorable to my reputation, I beg it may be remembered by every gentleman in the room that I this day declare with the utmost sincerity I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with. As to pay, Sir, I beg leave to assure the Congress that as no pecuniary consideration could have tempted me to accept this arduous employment at the expense of my domestic ease and happiness, I do not wish to make any profit from it. I will keep an exact account of my expenses. Those I doubt not they will discharge, and that is all I desire.

Washington's second-in-command

General Artemus Ward

Date and artist unknown

General Washington made preparations to leave for Boston. Those to serve under him were Major Generals Artemus Ward, Charles Lee, Phillip Schuyler and Israel Putnam. Eight brigadier generals were also commissioned. These were Seth Pomeroy, Richard Montgomery, David Wooster, William Heath, Joseph Spencer, John Thomas, John Sullivan and Nathanael Greene. At the General's request, Horatio Gates was appointed Adjutant General and given the rank of brigadier.