George Washington:

The Commander In Chief

Page 2

Before departing Washington wrote to his wife Martha:

You may believe me, my dear Patsy, when I assure you, in the most solemn manner, that, so far from seeking this appointment, I have used every endeavor in my power to avoid it, not only from my unwillingness to part with you and the family, but from a consciousness of its being a trust too great for my capacity, and that I should enjoy more happiness in one month with you at home than I have the most distant prospect of finding abroad.

The continental army at his command was growing on a daily basis. Thousands of farmers, fishermen, sailors, merchants, and artisans of New England, with very little discipline and much confusion, volunteered to serve the revolutionary cause.

In taking over the command on July 3, 1775, the Commander in Chief addressed the disparate army under his command, in his general orders of July 4, 1775:

The Continental Congress having now taken all the Troops of the several Colonies, which have been raised, or which may be hereafter raised, for the support and defence of the Liberties of America; into their Pay and Service: They are now the Troops of the United Provinces of North America; and it is hoped that all Distinctions of Colonies will be laid aside; so that one and the same spirit may animate the whole, and the only contest be, who shall render, on this great and trying occasion, the most essential Service to the great and common cause in which we are all engaged.

Washington's task was daunting. The Americans faced the well-equippend and trained British army, led by an experienced cadre of officers and generals. His own troops were mostly volunteers, only very loosely organized into seperate milita groups from the various colonies. He was tasked with forging these farmboys and fishermen into a fighting force to meet what was arguably the most powerful army in the world. Compounding their lack of experience, the Americans were poorly equipped, lacking arms, ammunition, adequate clothing, and artillary.

The Americans had scored an early victory in May with the surprise attack and capture of Fort Ticonderoga, and with it much needed munitions and supplies. Washington sent Colonel Henry Knox to bring 59 cannon from Ticonderoga. It was late in 1775. Winter was already upon them. The resourceful Knox managed to transport the massive artillary pieces using ox-drawn sleds. Washington used the captured artillary to fortify Dorchester heights, compelling General Howe to evacuate Boston, embarking his force for Halifax. The fleeing British left behind more cannons, small arms, powder and other supplies, an enormously welcome windfall to the ill-equipped Americans.

In July and August, 1776, General Howe and his forces arrived from Halifax, joined by his brother, Lord Howe, admiral of the British fleet, with over 300 ships largely full of highly trained German mercenaries. Sir Henry Clinton also arrived with troops from the south, and fully 30,000 veteran soldiers stood ready to annihilate the American Army, numbering no more than 18,000 men. The English planned to seize New York and then the rest of the country, quickly subdue the Colonials, and bring the war to a speedy end. As they landed and established themselves in and around New York, General Washington kept close watch upon their movements. He had 9,000 men in a fortified camp at Brooklyn, and on August 22, when he learned that the enemy had landed 10,000 men and 40 cannon at the lower end of Long Island. In his General Orders of August 23, 1776, he issued the following statement:

"The enemy have now landed on Long Island and the hour is fast approaching on which the honor and success of his army and the safety of our bleeding country depend. Remember, officers and soldiers, that you are freemen fighting for the blessings of liberty — that slavery will be your portion and that of your posterity if you do not acquit yourselves like men."

Despite Washington's inspirational leadership, the Americans failed to hold Long Island, though they did inflict heavy losses on the British before escaping to Manhatten, a deft retreat under cover of night and fog. The Battle of Long Island was the first major battle to occur after the colonies declared their independence. More troops were involved than in any other battle of the entire war. Although a defeat for the Americans, the successful evacuation prevented what would otherwise have doomed the entire revolution to failure.

Washington subsequently withdrew his forces from Manhatten Island and established them at White Plains, where they were attacked again by Howe's forces on October 28, 1776, and again executed a strategic retreat. Shortly afterwards, the American strongholds on the Hudson, Fort Washington and Fort Lee, also fell to the British. General Howe had dispatched his subordinate, General Cornwallis, to pursue the fleeing Americans across New Jersey, but On December 8, 1776, Washington and the army crossed the Delaware into Pennsylvania, once again narrowly escaping a crushing defeat by the British.

Howe and Washington were playing a game of cat and mouse, and the Americans were the mouse, continually fleeing from almost certain doom. Winter had come and American morale was waning. Washington conceived a plan for a bold attack that might boost American spirits: a surprise attack on the Hessian garrison at Trenton, across the frozen Delaware River, late on the night of December 25, taking the Hessians by surprise on December 26, 1776.

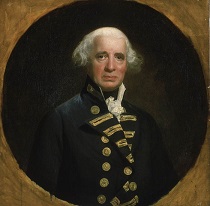

General George Washington at Trenton

John Trumbull, 1792.

The painting depicts Washington after the Battle of Assunpink Creek

also known as the Second Battle of Trenton

After the American victory at Trenton, soundly defeating the Hessians, Washington crossed the Delaware to Pennsylvania. He brought his troops across to New Jersey once again a few days later, setting up a defensive position on the Assunpink Creek, a few miles from Trenton. On January 2, 1777, the Americans repulsed a British assault, inflicting heavy casualties as the British repeatedly tried and failed to cross a bridge spanning the creek under heavy American fire. American familiarity with the terrain and their adoption of tactics appropriate to the dense woods surrounding the creek were decisive factors in the American victory.

The victory at Assunpink Creek was followed by another victory at Princeton the following day (January 3, 1777), capturing the city and many prisoners. This third defeat was enough for the British, who withdrew most of their forces from southern New Jersey. Washington and the Continental army spent the rest of the winter at an encampment in Morristown, NJ.

When spring arrived, the Americans and British resumed their skirmishing all along the Delaware and surrounding region, including the important battles of Brandywine and Germantown, culminating with the capture of Philadelphia, then the American capital. For a detailed examination of the chess game between General Howe and General Washington, see The Philadelphia Campaign: 1777